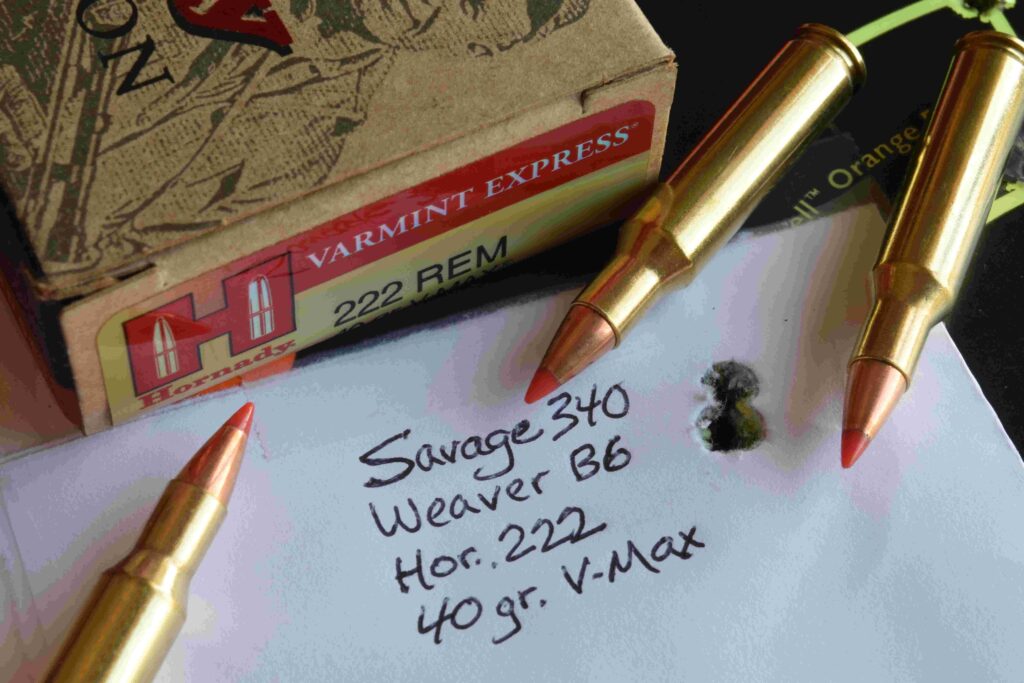

One-hole groups result when components and shooting routines don’t change.

“Great shot!” I meant it. Dust had spurted from the same rock his first bullet had pocked. “A hand’s width left.” My pal grinned from the mat as I pulled my eye from the spotting scope.

You might not think much of a couple of strikes a hands-width apart. But this Wyoming stone was 1,690 yards off. Nearly a mile. Drag had pulled the Berger HPBTs, started at 2,650 fps from the Sterling Precision rifle, through trans-sonic flight to a mere jog. Flight time: 3.2 seconds.

Accuracy is a measure of consistency, of perfect repetition. Good accuracy may be three shots in an inch with a hunting rifle – a minute-of-angle group. At 1,000 steps a minute of angle amounts to 10 ½ inches. Figure 18 ½ inches at a mile.

Uniformity in loads and shooting routine yielded this knot, from an inexpensive rifle and scope.

“Given wind currents over a mile of badlands, I’ll take a half-minute spread,” he replied.

There’s some luck at play when a second bullet lands that close to the first at that range. But you can shrink groups at any distance by making every shot as much as possible just like the last. At the mercy of shifts in wind speed and direction, you control loads and shooting routine.

“I use only Lapua brass to feed that six-five,” Royal Stukey told me. “Consistent weight and dimensions. And it takes Federal Gold Medal small rifle primers.” He’d bought hundreds of cases to get the same lot. “Some shooters won’t buy in bulk. I do that with powder, primers and bullets too. It helps ensure each load is the same as the next.”

“Match” die sets help you reduce variation in case sizing and bullet seating, for better accuracy.

Cases can vary in wall and web thickness, thus powder capacity, between manufacturers. There’s less variation among lots from one factory; but accuracy buffs batch hulls, setting aside those weighing half a grain over or under the mean. “Lapua brass doesn’t vary that much,” Royal assured me.

This affordable Forster neck turning tool makes necks concentric, their grip on bullets uniform.

You shouldn’t have to trim or de-burr fresh or once-fired hulls. But periodic checks later are useful. Keep batched cases uniformly at or just under specified length. To ease bullet seating, smooth their mouths inside and out with a de-burring tool. For consistent neck tension, measure wall thickness at four places around necks with a ball micrometer. More than .0015 variation in readings from one case is your prompt to outside-turn all necks in the batch. I use a Sinclair tool whose mandrel slips inside the neck. Spinning the case, I advance the cutter gradually as it takes off high spots. I stop just as the neck becomes uniformly bright. Concentric necks not only apply uniform tension; they enter “match” (minimum) chambers and center themselves in any chamber.

Powder now is very uniform, but accuracy buffs buy in quantity to avoid variation between lots.

Most flash-holes for large-rifle primers are punched to .082. Check with a #45 wire size drill bit. Some hulls, including 6mm BRs, have .060 flash-holes. De-burr all with a deburring tool inserted from the mouth. Ragged edges of punched flash-holes can deflect primer flame, affecting ignition. A depth gauge on the case mouth ensures you won’t cut into the web. Match hulls from Norma and Lapua have machined heads with drilled flash-holes. No need to de-burr.

Redding’s slant concentricity gauge shows “run-out,” helps ensure bullets are properly aligned.

Cull cases with visibly off-center flash-holes.

Bullets are more uniform than they were when Joyce Hornady started making them in the 1940s – though even then his accuracy standards were rigorous. “We test rifle bullets at 100,000-unit intervals,” I was told in a visit years ago. “The average of four five-shot groups must meet a standard. For .30s, that’s .600 at 100 yards, for 6mms it’s .450, for .338s .750. Those are hunting bullets. Match bullets are checked every 30,000 units, and the bar is higher: .350 for .22s. Our 30-caliber match bullets must shoot inside .800 at 200 yards.”

Shooting across badlands at a mile, you need uniform loads – and good wind-doping skills!

Vernon Speer, who worked with Hornady before WW II, set up his own bullet plant later in Lewiston, Idaho. His young brother Dick, a machinist at Boeing Aircraft in Seattle, joined him, tooling up to make specialty cartridge cases as Speer Cartridge Works. His extrusion process was sound, but the quality of raw stock varied widely. Meanwhile, handloaders whined they couldn’t get primers. In 1951 Dick hired Lithuanian chemist Dr. Victor Jasaitis to help him start producing primers for government contracts. To distinguish his shop from Speer Bullets, Dick and a partner changed its name to Cascade Cartridge, Inc. CCI soon outgrew its corner in Vernon’s bullet plant, so Dick bought a 17-acre tract near the Lewiston Gun Club. In a converted chicken coop under a tar-paper roof, he made rifle and pistol primers, adding shotshell primers in 1957 and rimfire rifle ammunition in 1963.

To reduce variables, buy the best components in bulk. Shooting position must be uniform too!

Outside a laboratory, variation in primers is hard to detect. Incidentally, magnum primers are not “hot.” They sustain their burn longer to ignite big charges of slow powder.

Meanwhile, John Nosler developed his Partition bullet, with core sections either side of a dam of jacket material. A hole in the dam of early machined Partitions jackets was not uniformly centered (a nit few if any hunters picked). Since 1970 jackets have been impact-extruded.

Long-range shooters use long match bullets, with tapered heels and hollow or poly-tip noses.

Nosler’s Zipedo bullet appeared in 1965, followed in ‘72 by the Solid Base. The Ballistic Tip unveiled in 1984 gave the family business a big boost. “We were the second North American firm to use a polymer bullet tip,” John’s son, Bob, told me. (Canada’s Dominion-brand Saber Tip came first.) Poly tips are now ubiquitous. Cosmetic upgrades, they reduce drag slightly and help start expansion. Nose profiles are more uniform than on most hollowpoints.

In prone competition, Wayne used Eley ammo, tested and bought by the lot to limit variation.

Despite their sleek form, bullets with long noses aren’t always more accurate than semi-spitzers or even blunt bullets. A Hornady engineer confided that that at ordinary ranges, modest nose shapes yield the tightest groups. His counterpart at Federal assured me a bullet’s ogive – the curve between tip and shank – has more influence on drag than does the tip. Tapered heels (boat-tails) reduce drag, but appreciably only at extreme range or in gale-force wind. And the additional angle is a variable. As most bullets used at distance are boat-tails, this trade-off is well accepted!

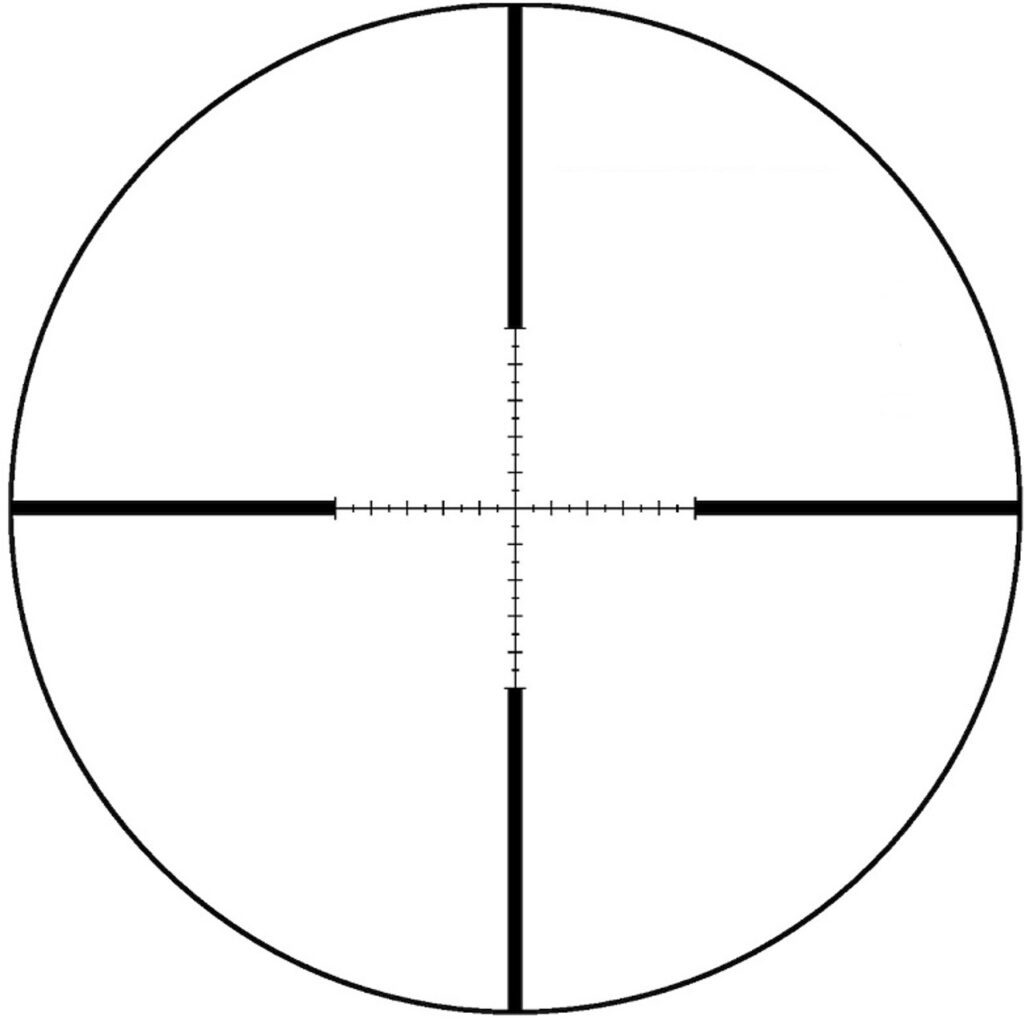

For precise aim, use a powerful, high-quality scope with a reticle marked in minutes or MILs.

A crimp is a variable too. It snugs the neck’s grip on cannelured bullets to prevent their creep in powerful and tube-fed rifles. While crimped loads can be accurate, most shooters chasing one-hole groups don’t crimp. Crimping dies are available for those who do; but a standard seating die suffices. With a bullet seated and the stem spun out so it doesn’t touch, bring the cartridge (in the press ram’s shell-holder) up into the die. Spin the die down until it stops. The die should now bear on the case mouth. Lower the ram, screw the die in a quarter turn and raise it again to press the die’s taper against the case mouth. Repeat until you get the crimp you want.

Your position (and all contact with and pressure on the rifle) should be the same, shot to shot.

You’ll find all manner of dies and tools to refine handloads. I’m sweet on Redding’s slant concentricity gauge (RCBS, Hornady and other sources have similar offerings). It measures bullet run-out as you spin the cartridge. A bullet started at an angle to the bore can’t be expected to land in the same place as one launched at a different angle or in perfect alignment.

Still, the most important variable in a shot is you. Whatever your cartridge components or loading practices and however accurate your barrel, where each bullet goes is most dramatically affected by how you hold and fire the rifle.

A long, hard, gritty or inconsistent trigger pull can move the rifle! Adjust or replace the trigger

For shots at rocks a mile off, Royal sandbags his rifle. For bench use, he builds massive, finely machined rifle rests with lapped adjustments that move silkily but absent detectable slack – the best commercial rests I’ve seen. However supported, your rifle must be held the same, shot to shot. Your hands and cheek must exert the same levels of pressure in the same places. In the field, shooting with a bipod, the forward press of your shoulder must be a constant. Using a sling, I try to ensure the loop’s placement and tension don’t change.

Refining your loads and shooting routine to eliminate variation pays big dividends afield too!

You can buy uniform ammunition and components from Midsouth Shooters Supply, also tools to measure uniformity. You can adopt a strict regimen assembling handloads. But a shooting routine that varies will send bullets to different places!