Spending big for a scope avails nothing if you don’t know what you’re looking for.

Muff a shot at a deer last fall? It’s a stretch to blame your rifle or your load. A deer’s chest is a big target. Wobbly aim and horsing the trigger are more likely culprits. The scope? Not if you installed and zeroed it carefully.

On the other hand, not all rifle-scopes are uniformly helpful. A rifle-scope can be an optical and mechanical gem without improving your odds of killing a deer – or even shooting a tight group from the bench! Bigger, heavier, costlier scopes with a fistful of features and adjustments can even handicap you!

Scopes appeared on rifles long after Galileo and Lippershay fashioned telescopes to help them see stars. But by the 1850s target shooters were aiming through dim barrel-length tubes at fuzzy bulls-eyes. Zeiss had a 2x prismatic sight in 1904, soon after the J. Stevens Tool Co. began making scopes in the U.S. Famed barrel-maker H.M. Pope used a 16-inch 5x model that listed for $24. By 1929 Winchester’s A-5 scope had become Lyman’s 5-A. Zeiss had acquired Hensoldt and was peddling 1-4x and 1-6x variables!

This old Weaver has a 3/4-inch tube, short eye relief. A pity this Winchester 92 was drilled to accept it!

Oddly, scope-makers proliferated during the Depression. In 1930, 24-year-old Bill Weaver built by hand a 10-ounce, 3x scope with a 3/4-inch steel tube and internal W/E adjustments (1-minute windage, 2-minute elevation). This Model 330 sold for a modest $19, complete with wire-like mount. It introduced a generation to optical sights.

About this time a Zeiss engineer found coating lenses with magnesium fluoride cut reflection and refraction, which bled up to 4 percent of incident light at each uncoated surface. Fog-free scopes followed after WW II, courtesy Leupold & Stevens in Oregon. All the while, scopes became relatively less costly! At $45 in 1940, the 2 ½x Lyman Alaskan with 7/8-inch tube, became hugely popular. A 4x Unertl Hawk of the mid-‘50s cost $2 less than Rudolph Noske’s excellent 4x had in 1939!

Marcus Leupold turned his company to making scopes in the ‘40s. No internal adjustments on this one.

In 1962, a year after Leupold trotted out its Vari-X 3-9x, Lyman announced Perma-Center reticles in its All American scopes. Soon W/E dials that sent reticles “off into a corner” of the field were obsolete.

By the way, variable scopes for U.S. sales have traditionally featured reticles in the rear or second focal plane. These remain one apparent size across the power range. First-plane reticles popular in Europe change size as you change power. Perversely, they can be hard to find at the low power settings you’ll use for close, fast shots in cover; and at high power they hide small, distant targets. Long-range plate shooters favor FFP reticles because their dimensions relative to the target remain the same at all power settings, so ranging is easy at any magnification. Also, there can be no reticle shift during power changes.

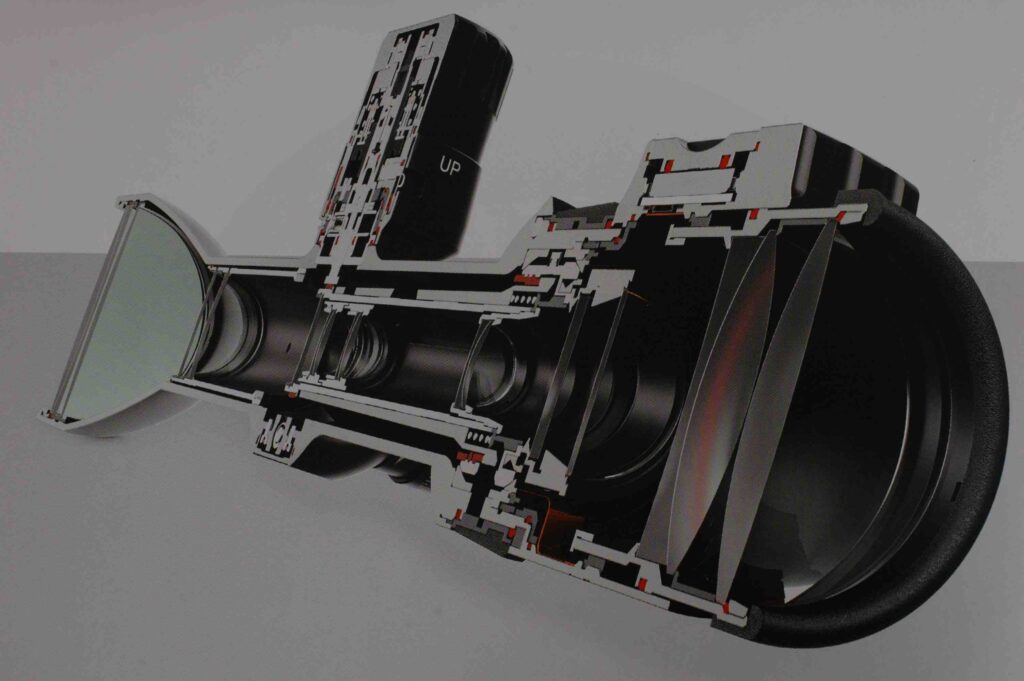

Top-quality high-power variables are expensive! Thank their complexity and superb multicoated lenses.

Grancel Fitz, who famously hunted all species of North American big game from the late 1920s into the ‘50s, had a Hensoldt 2 ¾x scope on his Griffin & Howe .30-06. By the end of his quest, the 4x scope with 1-inch tube had become hugely popular. Weaver’s K4 sold for $49.50. As variables upstaged fixed-power scopes, hunters lusted for higher magnification and wider ranges. The 3-9x with three-times power range (top power three times the bottom) gave way to the 4-16x (four-times). Now there are scopes with five- and six-times ranges. High power makes precise aim easier at distance; but to adjust for bullet drop far off, tubes must be bigger (more dial movement). Hence, the 30mm to 36mm scopes now offered.

Boosting magnification reduces light transmission. A scope’s exit pupil – the diameter of its front lens in mm divided by the power – is a measure of the shaft of light reaching your eye. A bigger EP yields a brighter image. A healthy human eye dilates to about 6mm in very dim shooting light. A 3-9×36 scope has a 12mm EP at 3x power: more light than your eye can use. Its 4mm EP at 9x becomes limiting only in poor light. With its larger 50mm objective, a 3-9×50 scope has an EP of 5.5mm at 9x.

Any scope is faster, more accurate to use when you focus the reticle for your eyes. Adjust that eyepiece!

Another value, relative brightness, is the EP squared. A 4×40 scope has an EP of 10, so a relative brightness of 100. An 8×40 scope’s relative brightness (EP = 5) is 25.

Twilight factor is arguably more useful. The square root of the product of the magnification and objective lens diameter, this number reflects how well you’ll resolve detail in dim light. It increases as you turn up scope power. For example:

Scope power, objective diameter Exit pupil Twilight factor

2 ½ x20 8mm square root of 50, or 7.1

4×20 5mm square root of 80, or 8.9

2 ½x24 9.60mm square root of 60, or 7.7

4×24 6mm square root of 96, or 9.8

8×40 5mm square root of 320 or 17.9

10×40 4mm square root of 400 or 20

8×50 6.25mm square root of 400 or 20

10×50 5mm square root of 500 or 22.4

Note that at 2 ½x a 1 ½-6×24 scope has a twilight factor of 7.7; but at 4x the twilight factor jumps to 9.8, while the EP dips from 9.6mm to 6mm. As regards resolution in dim light, the added magnification more than offsets the drop in brightness. As your eye can’t use a 9.6mm shaft of light, there’s no practical difference in EP. (Of course, in very low light, a high twilight factor with a small EP won’t help you aim.)

Burris’ Fullfield 3-9×40 and (here) 2-7×32 are lightweight, top-value hunting scopes, best in low rings.

Note too that a 3-12×40 scope set at 10x has a twilight factor of 20, while a 3-12×50, its objective lens 25 percent bigger, delivers a twilight factor of 20 at 8x. Again, resolving detail in dim light, you need a 25 percent increase in front lens diameter to equal a 20 percent boost in magnification.

Increasing objective size has practical limits. Bigger glass adds weight, bulk and cost to the scope and mandates use of medium or high rings to keep the front bell off the barrel. Lifting your face from the stock to aim, you’re less comfortable and less accurate. Still, the current market shows that many hunters find high-power scopes irresistible, despite liabilities imposed by their heft and dimensions.

Other hunters, especially those prowling thickets or on the steeps, favor slim, lightweight scopes, like Leupold’s VX-3HD 1 ½-5×20. It weighs less than 10 ounces. (My own rule of thumb: for good rifle balance and to keep center of gravity low, a scope shouldn’t scale over 15 percent of the rifle’s weight.)

Midsouth Shooters Supply carries optically superb Meopta scopes, here a versatile mid-range variable.

Besides their wide, bright fields of view, and svelte tubes, such low-power scopes have generous eye relief: Your eye needn’t be as near the lens as with high-power scopes. ER is also non-critical: Your eye has more latitude, fore-and-aft, to get the full field. Lyman’s 2 ½x Alaskan had 3 to 5 inches of ER. Eyepieces on current high-power variables are longer and bulkier, while ER is shorter and more critical.

Modest magnification also speeds your shot, both by showing you the target quickly and bringing an acceptable sight picture sooner. It spares you the exaggerated reticle movements of high-power glass. Time and energy spent trying to tame twitches and pulse bounce delay the shot and cause more motion as your muscles tire. At modest magnification, you more easily ignore little hops as you squeeze the trigger.

This trim 3-9×33 Leupold is engineered for rimfire rifles; it’s adjusted to zero out parallax at 75 yards.

In the same way high scope power can show more mirage than is useful for judging bullet drift. You want to see mirage. You don’t want it so distorting the target image that you can’t confirm its center!

The best magnification in a hunting scope depends on expected distance, target size and shooting position. I have shot only two big game animals that couldn’t have been handily killed with a 4x scope. Remember: At 4x a deer 400 yards off appears the same size as it would with the naked eye at 100!

Features like parallax dials, lighted reticles and load-specific W/E dials? They’re grist for another column. Meanwhile, you’ll find myriad scopes, from Burris to Vortex, at Midsouth Shooters’ Supply.