The barrel stamp tells you what cartridges to buy – doesn’t it?

Rifle and handgun barrels and chambers are cut to close tolerances. Any given cartridge is made to fit a chamber of specific dimensions. The headstamp on the case should match the stamp or inscription on the barrel. But it doesn’t always. Sometimes the numbers differ but the cartridge fits and fires safely. Sometimes the numbers are the same, but the cartridge won’t chamber, or it chambers loosely so is not a safe fit. What gives?

Since their inception around the time of our Civil War, metallic cartridges have been labeled for their dimensions. But the numbers don’t all refer to the same dimensions – or represent the same unit of measure! Other numbers can be added: year of origin, powder charge, bullet weight, even velocity.

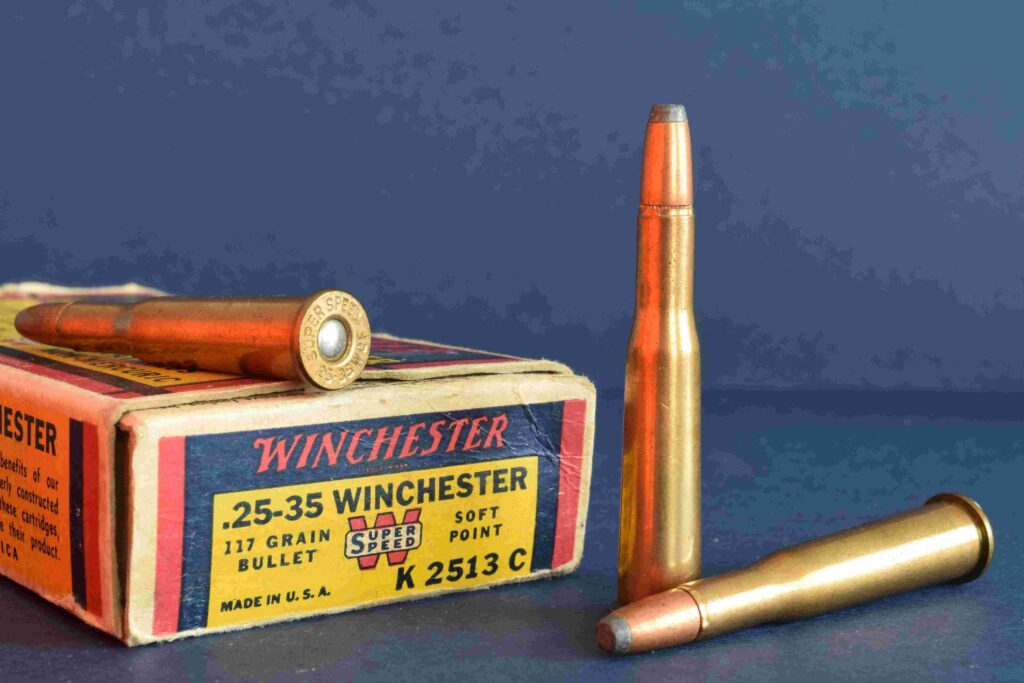

The .25-35 arrived with smokeless powder but kept old labeling: bullet diameter/black powder charge.

The .25-35 arrived with smokeless powder but kept old labeling: bullet diameter/black powder charge.

Box labels commonly specify the cartridge by number and name. The manufacturer is a name that has nothing to do with the dimensions of the cartridge. A .243 Winchester cartridge by Remington has the same case dimensions and bullet diameter as a .243 Winchester load by, well, Winchester. Or Federal. Or Norma. Traditionally, numbers refer to one of two diameters in the barrel. Bore diameter across the lands is the interior diameter before it is rifled – before the spiral grooves are cut. Groove diameter (essentially, bullet diameter) is also used as “caliber” designation. Example: the .250 Savage and .257 Roberts rifles both send bullets .257 inch in diameter, from .250 bores. A 30-caliber or .300 barrel has a .300 bore .308 across the grooves. So do the .308 Winchester and .308 Norma Magnum. So bullets .308 in diameter are used in all 30-caliber barrels, including .300 magnums.

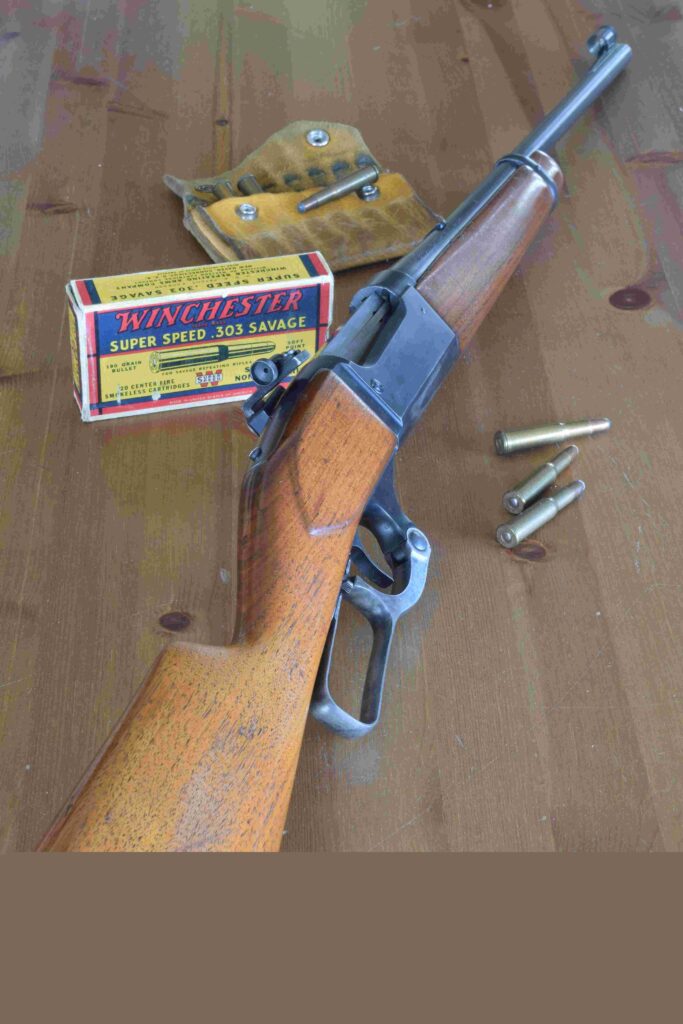

This 1899 Savage rifle in .303 Savage uses .308-diameter bullets, not .311s like the taller .303 British.

What distinguishes a cartridge are its case shape and dimensions, which must suit the chamber, with tolerances. The .300 Savage cartridge differs from the .300 Blackout, the .30-40 Krag from the .30-06. All .300 Magnum cases differ from each other, so none interchange with the others.

Some cartridges don’t follow the rules, however. A rifle in .303 British fires .311 bullets, but my Savage carbine in .303 Savage takes .308s. In handguns, the .380 ACP uses the same .355 bullets as the .357 SIG. The .41 Magnum hews to logic with its .410 bullet, but a .41 Long Colt’s is .386 in diameter!

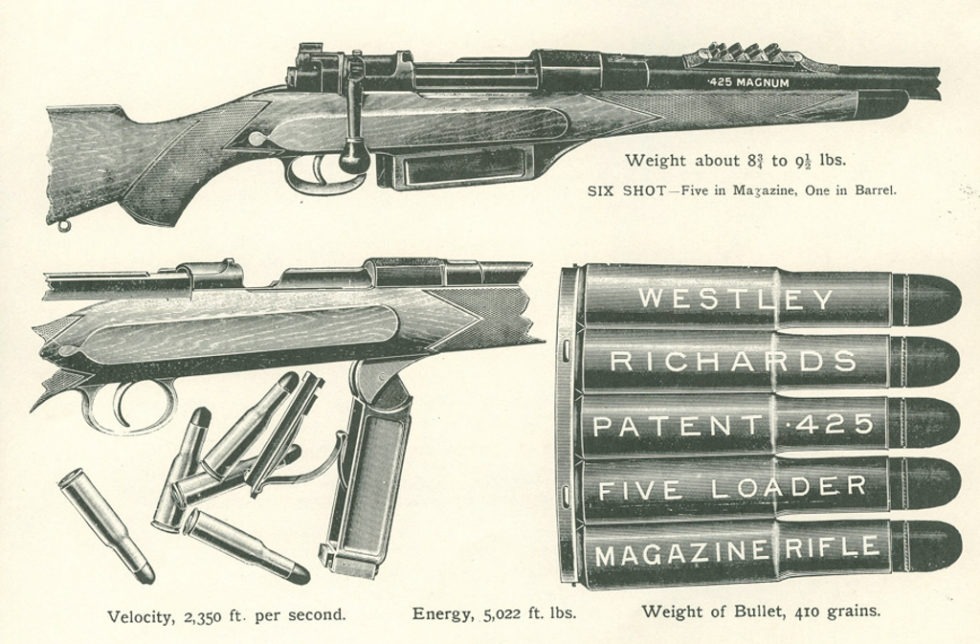

In 1909 Westley Richards named its .425 Magnum per later U.S. custom. The .425 case rim is rebated.

A pair of two-digit numbers usually shows the cartridge predates smokeless powder. The second numbers indicate grains, weight, of black powder in original loads. (There are 437.5 grains in an ounce.) Here too there are rule-breakers. The .38-55 is served by .375 bullets, the .38-40 by .401s. The .30-06, smokeless from the start, is of 30 caliber, but the “06” denotes the year of adoption by the U.S. Army: 1906. Some black-powder cartridges are given a third set of digits, the last denoting bullet weight (.45-70-405) or case length in inches (the .45-120-3 ¼ -inch Sharps).

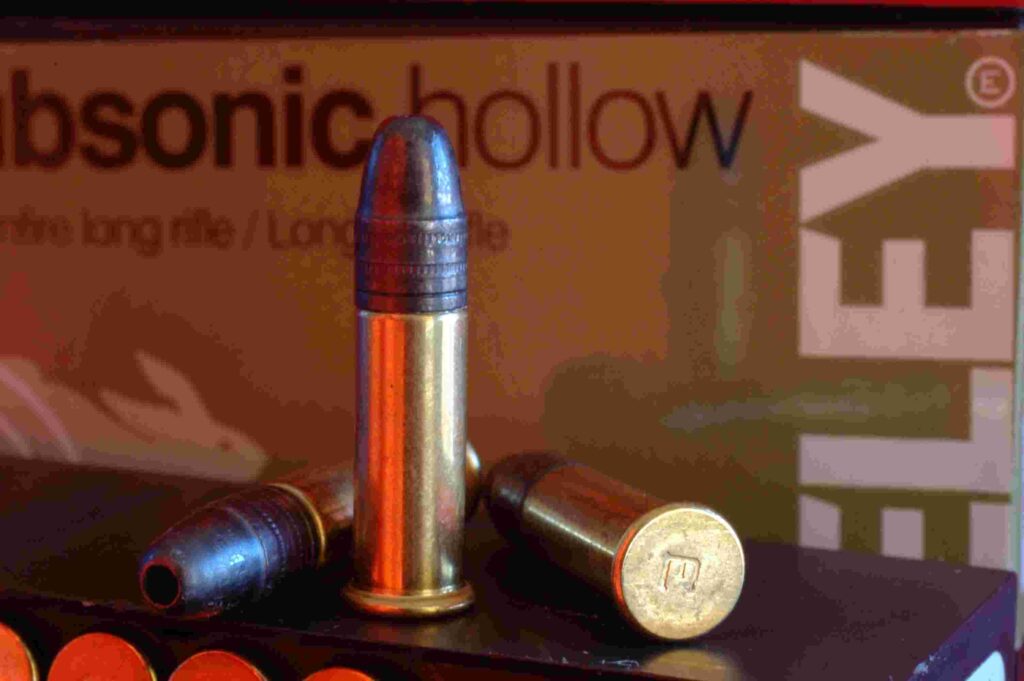

The .22 Long Rifle dates to 1887. Now countless LR loads (here Eley subsonic) fit .22 LR chambers.

Another anomaly: the .250-3000 Savage. Developed by Charles Newton in 1913, it sent 87-grain bullets at an advertised 3,000 feet per second – eye-catching speed in that day.

Savage named Charles Newton’s .250 (circa 1913) the .250-3000 to hawk the bullet’s blazing speed.

While boxes of sporting ammunition generally have all the information you need to match it with the proper rifle, military loads may lack helpful packaging – or even revealing numbers on the headstamp.

Headstamps of infantry ammo produced during war-time may seem indecipherable. Widely spaced digits may indicate place and year of manufacture. Example: L C 4 3 for Lake City Arsenal, 1943.

Barrel stamps and inscriptions can also confuse; “.30 U.S.” may mean the rifle is chambered for the .30-40 Krag, adopted by the U.S. Army with the Krag-Jorgensen in 1892. But the .30-03, then the .30-06 followed, in the 1903 Springfield. Some stamps have clarified: “.30 Gov’t 06.”

The .270 Winchester (left) turns 100 this year. Not until 1943 did Roy Weatherby announce his belted .270 Magnum. The short .27s here – .270 WSM and 6.8 Western – followed in the last 25 years.

Long ago, before .300s became a herd, the British firm of Holland & Holland had the only such cartridge. In 1937 Winchester stamped its first Model 70 barrels simply “.300 Magnum.” An “H&H” was superfluous at the time. Soon it was mandatory.

The Teutonic habit of designating bores in millimeters has come stateside, albeit not always with the case length in mm, per Europe’s 9.3×62. The 6mm Remington (.243 bullet), 6.5 Creedmoor (.264) and 7mm Dakota (.284) lack it. NATO rounds (the 5.56×45 and 7.62×51) have it. The 7×57 or 7mm Mauser has a British name too: the .275 Rigby. The German 12.7×70 is another name for the British .500 Jeffery. Name changes add confusion. Remington’s 6mm was first its .244, the switch prompted by a change in rifling from one turn in 12 inches to one-in-9, to better stabilize 100-grain bullets. The .243 Winchester, ballistic twin to the .244, was snaring market share with 100-grain loads that shot well from Winchester’s 1-in-10 rifling. To shed the .244’s baggage, Remington put a new headstamp on the cases, gave barrels a fresh stamp to match and offered 100-grain loads in its “new” 6mm

This is a .25 Short Krag, a wildcat on the .30-40 Krag case. The barrel on this Winchester High Wall should be so marked, to ensure the chamber has proper headspace for the cartridge.

For no reason I can think of, the .280 Remington became the 7mm Express – then the .280 again! From its root, “Magnum” suggests high performance. “Nitro Express” is the British equivalent. It derives from “nitroglycerine” (in double-base smokeless powder) and followed “Black Powder Express,” a label Purdey launched in the 1850s to give its new big-bore rounds the image of a hurtling locomotive. A British “nitro proof” stamp indicates the rifle has passed pressure tests with smokeless powder.

Incidentally, dual numbers for British cartridges name the parent cartridge first, the bore next, in reverse order from the custom stateside. A .450/.400 NE derives from a .450 cartridge, necked down.

Per European tradition, the .577/450’s name lists the parent cartridge first. A 19th-century British army cartridge, it may carry only a military headstamp, with no information to match it to a barrel stamp.

Rimfire rifle and handgun cartridges predated centerfire. The .22 BB Cap arrived in 1845, its ball powered only by priming in what were then known as parlor rifles. The CB cap in its wake was the BB Cap with a pinch of powder. The .22 Short, follow-on to an experimental revolver cartridge by Smith and Wesson, appeared in 1857, the Long in 1871. The Long Rifle came in 1887. All used outside-lubricated bullets. A .22 LR rifle or handgun will safely and accurately fire S or L loads; but some LR mechanisms don’t cycle reliably with the S and L. In 1977 CCI released Stinger ammo, with a longer case than the LR, and a lighter, faster bullet. Firearms bored for the .22 LR accept Stingers – and similar Remington Yellow Jacket and Winchester Xpediter loads.

The .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire, introduced in 1959, has a longer case than the .22 LR. It is also bigger in diameter, to clasp a jacketed bullet whose shank is smaller in diameter than the case. The .22 WMR will safely fire the now-obsolete .22 WRF and .22 Remington Special.

Both these loads fire in .38 Super pistols, but the “+P” load should be used only in strong modern guns.

Sidebar: Common interchangeable cartridges

(Note: Cartridges that chamber in repeating firearms marked for others may not cycle reliably!)

.22 Short and .22 Long in .22 Long Rifle chambers

.22 Winchester Rimfire and .22 Remington Special in .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire chambers

.223 in 5.56 NATO and .223 Wylde chambers *

5.56 NATO and 5.56×45 (same)

.244 Remington and 6mm Remington (same)

.250 Savage and .250-3000 (same)

.25-35 Winchester in .25-36 Marlin chambers

.280 Remington and 7mm Remington Express (same)

.308 and 7.62×51 NATO (essentially the same; interchangeable)

7×57 and 7mm Mauser and .275 Rigby (same)

9×19 and 9mm Luger and 9mm Parabellum (same)

.38 Colt Automatic in .38 Colt Super Automatic (same; but later, potent .38 Super not for early pistols)

.38 Long Colt in .38 Special chambers **

.38 Special in .357 Magnum chambers (both also in .357 Remington Maximum chambers)

.44 Russian and .44 Special in .44 Magnum chambers

.45 Long Colt in .454 Casull chambers

The .223 and 5.56 NATO chamber in rifles marked for either, but pressures of most commercial loads differ, as do rifle throats. Standard caveat: Use 5.56 NATO ammo only in rifles so marked.

* The .223 dates to 1957 as an experimental cartridge for the Armalite AR-15 rifle, Adopted by the U.S. Army in 1964, it served in Vietnam as the 5.56mm Ball cartridge M193. In 1980 NATO countries substituted FN’s SS109 62-grain boat-tail bullet. The cartridge became the 5.56 NATO or 5.56×45.

Sporting rifles in .223 Remington (same case dimensions) were given a shorter throat (freebore forward of the chamber) and a steeper leade (entering angle of the lands) to improve accuracy. Soldiers didn’t need tight groups; but their M16s had to cycle with dirty ammo and long tracer bullets. Generous chambers in infantry rifles also kept a lid on pressure when automatic fire made barrels glow.

Winchester adopted the .308 in 1952, after the U.S. Army had developed it as the T-65. Sporting rifles in .308 came right away. Army adoption followed in ’54. In military circles it’s now the 7.62×51 NATO.

The .223 and 5.56 will chamber in barrels marked for the other. But differences remain in rifles and ammunition. While the .223 is loaded to 55,400 CUP (Copper Units of Pressure), service 5.56 NATO loads can generate 58,000. SAAMI has warned against use of 5.56 ammo in .223 barrels. Some .223 rifles are claimed to fire 5.56 cartridges safely. The .223 Wylde chamber was developed to fire both accurately.

** Some .38 L.C. chambers have accepted .38 Spl. even .357 Mag. loads, hazardous if fired in them.

The .30-06 (left) became the U.S. infantry cartridge in 1906. The .300 H&H Magnum arrived in 1925. Roy Weatherby reshaped it in 1945 to form his .300 Magnum. Winchester’s .300 Magnum dates to 1963.

A number of old black-powder cartridges were interchangeable in rifles bored for others. The .56-50 Spencer used briefly in our Civil War is nearly identical to the .56-52 Spencer that followed. Long and short versions of rimfire black-powder cartridges were quite common, short options firing safely in long chambers. Some straight-case, rimmed smokeless cartridges follow that pattern. The .38 Special will fire safely and accurately in .357 Magnum revolvers because the bullets for both are .357 in diameter, and the cases share base and neck diameters. The .38 Special case is .13 shorter than the .357 Magnum’s. For the same reason, .44 Special ammo works fine in.44 Magnum chambers. This compatibility does not exist for long and short bottleneck rifle cases that headspace on the shoulder.

All 6.5mms, many of these came long after a spate of military 6.5s, 1891-1905. Cartridges here (L-R) match boxes clockwise from lower left. Far right: 26 Nosler and 6.5-.300 Weatherby Magnum.

Headspace is a critical measure that defines the relationship between the cartridge and its seat in the firearm. It’s not the size of the chamber. It is the distance from the face of the locked bolt to a datum point (in truth a circumferential line) in the chamber that arrests the forward movement of the cartridge. Upon firing, the striker’s blow pushes the cartridge forward until it contacts the datum point. Case expansion irons the front of the case, but not the thicker head, to the chamber wall. The case stretches as gas pressure leveraged against the bullet and case shoulder presses the head against the bolt face. The case wall forward of the head can stretch a little without damage. But excess headspace can permit it to stretch too far, even separate. When that occurs, high-pressure gas moving faster than a bullet zips into the striker hole, along the bolt race and through tiny openings. It can blow pieces off the action and split the stock.

The term “headspace” originated when all metallic cartridges had rims, so the first measurements were made only at the head. Headspace is still gauged from the bolt face, but the datum point varies with cartridge design. A rimmed case (think .30-30) is arrested by the rim, a belted magnum by the front edge of the belt. The “stop” for rimless bottleneck cartridges like the .308 is at the shoulder. A straight rimless case like the .45 ACP’s headspaces at the mouth. Straight semi-rimmed cartridges may headspace on the rim, but the rim on some cases, like the .38 Super Automatic’s, is insufficient given the action tolerances required for sure function. The case mouth then serves as a stop.

Rifles properly bored for Improved cartridges have the headspace measure of the parent cartridge. That’s why you can safely fire factory ammo in an Improved chamber.

Standard caliber designations have a decimal up front. Nosler chose not to use it in its line, here a 28.

Repeated handloading “work-hardens” brass, reducing its ability to stretch. Then cases can split in actions within acceptable headspace tolerances. To preserve the elasticity in their cases and extend their life, many handloaders size only the necks of bottleneck cases. The semi-rimmed .220 Swift is commonly neck-sized to headspace on the shoulder, though its rim is substantial.

Cartridge designers go to great lengths to fashion cases that won’t fit snugly in rifles chambered for different ammunition. Body taper, shoulder location and of course head type and diameter can be used to stall the insertion of cartridges where they don’t belong. But some incorrect rifle/cartridge pairings give no warning that something is amiss. And the result can be violent.

The new .360 Buckhammer uses .358 bullets, like the .35 Whelen, .350 Remington Magnum, .356 and .358 Winchester and .358 Norma Magnum.

I was warned early against leaving 20-gauge shotshells in an upland vest when using a 12-gauge gun. “Excited by squadrons of rooster pheasants rocketing off, you might without looking toss a 20-gauge shell into the breech. It will slip ahead to the chamber mouth, where the rim will hang up. The gun won’t fire, and a glance shows nothing in the breech. You then load a 12-gauge shell and fire. The charge gets as far as the 20-gauge shell and detonates it. The pressure shreds the barrel, possibly your forward hand.” Mismatched rifle ammo can cause problems too. A .308 cartridge chambered easily in a friend’s .270, because in chambering, the shorter cartridge’s bullet didn’t reach the throat. The extractor held the case head against the bolt. Firing forced the .308 bullet into a .277 bore. Exceedingly high pressure split the case, spilling gas that locked the bolt, blew the extractor off and reduced the walnut stock to kindling.

Take care that the ammo you load matches the inscription on your barrel, or is a vetted substitute!