.32 caliber handgun cartridges wax and wane in popularity with the times. Generationally, the .32 becomes a platform defining option before it becomes a fad as other trends prevail for a period. After several decades of relative obscurity, the .32 and both its virtues and issues, have made a comeback. Walther has recently brought back their legendary PP and PPK in .32 ACP. At SHOT Show 2025, Beretta introduced their 80X in the same cartridge. Ruger, Charter Arms, and Taurus kept the coals of the .32 revolver market going until Smith & Wesson, with input from Lipsey’s, brought in the 432 and 632 Ultimate Carry revolvers. Dozens of .32 caliber cartridges have been offered throughout the years and both .32 ACP and .32 H&R Magnum are enjoying a rising tide of popularity. But the .32 S&W Long cartridge dwarfs the rest in terms of availability and history. It also helps that it is still an efficient cartridge more than 120 years after its introduction. Here is a snapshot into the history and ballistics of the .32 S&W Long and why you might want to snag a box or two.

The .32 S&W Long debuted with a 98 grain lead round nosed bullet, but wadcutter and even hollow point ammunitions have long been available

The .32 Long in Context

Since Samuel Colt launched his Pocket Model revolver in 1849, .32 caliber handguns were prized among those who needed a concealable hideout gun without sacrificing too much hitting power. That handy compromise carried over to the cartridge era with rounds like the .32 rimfire and the .32 S&W. The latter was introduced for the Smith & Wesson No. 2 pocket pistol in 1878. The .32 S&W is a rimmed centerfire cartridge that carried a .312 inch diameter 90 grain lead bullet backed by up to nine grains of black powder.

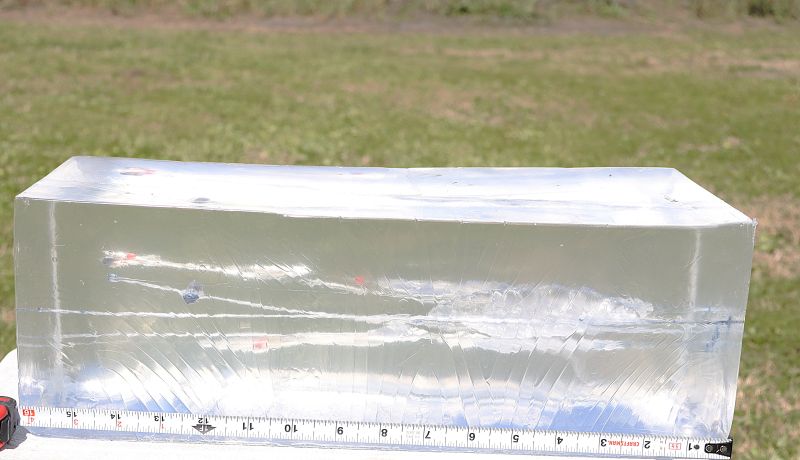

A block of Clear Ballistics 10% gelatin peppered with .32 H&R Magnum Hornady Critical Defense ammunition and Fiocchi 100 grain .32 Long wadcutters. Out of the short 1 7/8 inch barrel of the S&W 432 UC, the wadcutters travel at a sedate 620 feet per second, but two out of the three rounds fired tumbled and traversed the entirety of the sixteen inch block after punching through four layers of denim. One round stopped short at a respective 13 inches.

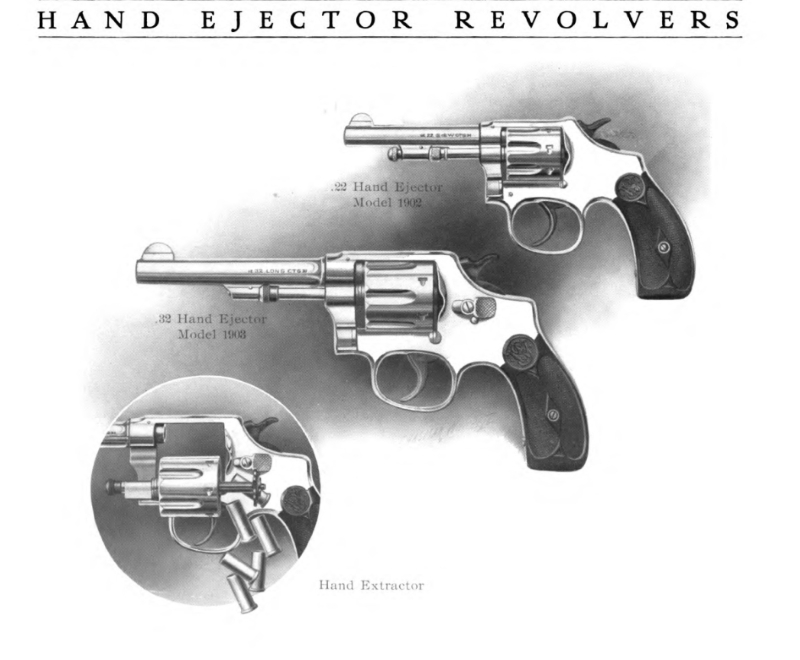

The .32 S&W enjoyed decades of popularity despite its size and strength, particularly in tiny top break revolvers like the S&W New Departure and the Iver Johnson Safety Automatic. Out of the Iver Johnson’s 3 inch barrel, that 90 grain bullet travels at about 650 feet per second for 84 foot pounds of energy. Despite that, guns chambered for this little round lined many pockets and was considered a legitimate police cartridge, particularly in the Eastern beats. But the desire for stronger handguns and cartridges to match at a given size is a march that continues onward. The 1890s saw the rise of solid-frame swing-out cylinder revolvers. Smith & Wesson later dominated this market, but during much of that decade, the company stayed off the market, leaving the market to Colt. But in 1896, Smith & Wesson responded with their Hand Ejector revolver. It was the first Smith & Wesson revolver to feature a swing out cylinder and simultaneous ejection via a hand ejector rod. It was also chambered in a new, more powerful cartridge: the .32 S&W Long.

The .32 S&W Short was a respectable pocket pistol cartridge in guns like this Iver Johnson Safety Automatic. But stronger guns invite stronger cartridges.

The .32 S&W Long was so named to differentiate it from the .32 S&W, now often called the .32 Short. The .32 Long had an identical case head and rim of the .32 S&W with a longer .92 inch case. The bullet is the same diameter, but the mass was increased to a 100 grain lead bullet with more powder, resulting an extra 100 feet per second over the Short. As an added bonus, the new Hand Ejector from Smith & Wesson was little bigger than existing .32 Short revolvers.

The potential of the cartridge was seen immediately by Smith & Wesson’s competitor, Colt. That same year, Colt introduced the New Police chambered in .32 Colt New Police. That cartridge is identical to .32 S&W Long save that it used a flat-nosed instead of a round-nosed bullet.

The .32 S&W Long grew in popularity, particularly with Eastern police departments after the NYPD standardized on the cartridge in the Colt New Police and later Colt Police Positive revolvers starting in 1896.

The .32 S&W Long has a reputation for competition grade accuracy with a long-for-caliber bullet and low felt recoil. Here is a rapid-fire six-shot cluster posted at ten yards with the S&W 432 UC.

The easy shooting low-recoiling .32 Long would be considered a very underpowered round for police work, but in its day it was considered superior to what was once classed as sufficient. But new threats were always emerging in an arms race with the criminal element. Revolvers chambered in .38 Special like the Smith & Wesson M&P and Colt Police Positive Special were somewhat larger than the .32, but easy for belt carry. The .38 was also a better cartridge, particularly as automobiles became part of day to day police work.

In the depths of the Depression, the .38 Special had largely supplanted the .32 Long, but the cartridge continued to be offered in small and medium-framed revolvers from Colt and Smith & Wesson for decades for small departments and public sales. The round also grew in popularity with competitors within the International Shooting Sports Federation. Its international appeal has only grown as domestic interest waned. Manurhin and Alfa Proj produce runs of revolvers in .32 S&W Long and Hammerli even produces a semi-automatic target pistol geared toward .32 S&W Long wadcutters.

The Case for the .32 S&W Long Today

Although available in medium-framed revolvers, .32 caliber revolvers tend to be small-framed. This class boasts less felt recoil with a six-round cylinder instead of the five rounds afforded a typical .38 Special or .357 Magnum revolver. Attempts to up gun the .32 Long resulted in the development of the .32 H&R Magnum and the .327 Federal Magnum. The case for the .32 Long is usually made in revolvers chambered in these other cartridges.

From left to right: .22 LR, .32 S&W, .32 S&W Long, and .38 Special.

The .32 S&W Long can headspace off of its rimmed case and both fire and eject in revolvers chambered for .32 H&R and .327 Federal. Although handloaders and boutique makers like Buffalo Bore have hot-rodded it to rival its bigger brothers, the .32 S&W Long on the whole is lower powered boasting between 100-150 foot pounds of energy. It is comparable to .22 LR fired from a rifle barrel and slightly less than conventional pistol cartridges like .380 ACP. The compensation for this tradeoff against its relatives and other cartridges is lower felt recoil, relative cost-effectiveness, and surprising bullet performance.

A vintage advertisement for Smith & Wesson’s I-frame and K-frame revolvers in .32 S&W Long. [The Revolver: For the Pocket, for the Military, and For Targe Practice, Smith & Wesson, (Springfield Mass, 1905)]

The .32 Long is prized for its low felt recoil. It is a firm step above cartridges like .22 LR and .22 Magnum in a handgun thanks to its higher power and centerfire reliability. It also lacks the snappiness of rounds like .327 or .380 and even the relatively sedate .32 H&R. This results in quicker follow-up shots as needed and great accuracy to boot. It is also contusive as a practice round. Although not as commonly available as .380 or 9mm Luger, the .32 S&W Long is more available in different loadings at lower cost than newer .32 cartridges thanks in large part to its history and popularity in competitive bullseye shooting. But to conclude that you are getting an underpowered practice ammunition for your .32 revolver that is conducive towards new shooters is also a mistake. It boasts a nominal 100 grain bullet, which is long for caliber compared to other .32 caliber pistol rounds like .32 ACP, .32 S&W, and even some .32 H&R loads. It is a little heavier than comparable .380 rounds. At the low velocities the Long operates, bullet expansion is minimal. What is gained in the trade-off is surprisingly good penetration that exceeds what some .32 Magnum, .380, and .38 Special loads can do.

Whether you are looking at putting an old J-Frame or Police Positive into service or weighing the latest snubbies, the .32 S&W Long cartridge makes for an excellent practice round in .32 caliber revolvers thanks to its negligible recoil and low cost. But with a track record that is miles long and terminal ballistics that are better than its paper energy number suggest, the .32 Long is a practice round that can easily double as a primary load.