Knowing the speed of your bullets has always been helpful. With Doppler radar it’s now easy!

Webster’s says a chronograph is “any of various instruments for measuring and recording brief, precisely spaced intervals of time, as a stopwatch.” A definition not unexpected. “Chrono,” after all, is a reference to time, as in “chronology” and “chronometer.”

But as a shooter, you want to know velocity, or speed. A bullet’s velocity affects its trajectory and energy, even its accuracy. And it relates directly to what pops the bullet free in the first place: the pressure from gas produced by burning gunpowder. At some point, hiking bullet speed requires more pressure than the cartridge case or the firearm can safely handle.

This chronograph measures the time a bullet spends between precisely placed screens under shades.

Time is a factor in measuring speed, as is distance. A marathoner spools out 26.2 miles as quickly as possible. Elapsed time at the finish line determines the runner’s ranking, as all competitors must travel the same course. High speeds are more practical to gauge and express with time as the constant, distance the variable. So we cite automobile speed in miles per hour, bullet velocity in feet per second.

All motorists mind speedometers. But now a police officer a mile away can point a radar gun and read what’s on my dash. While Doppler radar has been used to measure bullet velocity for several years, only the likes of ammunition makers could afford this technology. Now Garmin and LabRadar offer that option in compact, affordable units for shooters. You’ll find them at Midsouth Shooters Supply.

The magic was a long time coming.

In 1537 a smart Italian named Trataglia suggested in his book on ballistics that balls hurled from firearms arced to their targets. The prevailing belief then was that they flew straight, dropping abruptly to earth out yonder. Similar logic held that ships eventually fell off the edge of the ocean.

Dr. Ken Oehler’s portable, accurate, affordable chronographs (here a 35P) have enlightened shooters!

Trataglia concluded a barrel tilted to 45 degrees would send balls furthest. That’s steeper than we would elevate a .270’s barrel. But his thinking was valid for the big, slow projectiles of his time, reined in almost entirely by gravity. He couldn’t have imagined the drag set up by bullets at Mach 3. Neither could Galileo, dropping cannon balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa in 17th-century studies of ballistics.

By the early 1700s Sir Isaac Newton would show a relationship between drag and the square of a bullet’s velocity. Roughly 15 years after Newton died in 1727, Englishman Benjamin Robbins developed a ballistic pendulum, with a wooden bob of known weight. Firing a bullet, also of known weight, into the bob and measuring its swing yielded the information Robbins needed to approximate the bullet’s velocity. But there were doubters. How could a musket ball accelerate to 1,500 fps? And surely diminished swings at distance didn’t really mean drag exceeded 80 times the force of gravity!

Late in the 19th century, studies by Krupp in Germany and the Gavre Commission in France led a Russian colonel, Mayevski, to fashion a drag deceleration model with a Krupp bullet three calibers long. In 1893 U.S. Army Colonel James Ingalls followed with his first Ingalls Tables. The Krupp was the first “standard bullet” used to develop ballistic coefficients, which changed markedly near the speed of sound.

Soon ammunition makers were installing electronic chronographs, which measured the time lapse as a bullet passed between two electric eyes or invisible “screens” a precise distance apart. Engineer and handloader Dr. Ken Oehler tapped this technology to build a chronograph in a metal box he’d picked up for 50 cents at an Army dump. From it came the Oehler Model 10. The Model 33 followed. A Model 82, conceived while he waited for deer under an oak, harnessed the power of personal computers. In 1988 the 35P set a standard in personal chronographs. It yields a wealth of data instantly. Unlike less sophisticated chronographs of its type, it has three “eyes,” shielded from glare by translucent shades. Shooters get two reads per shot. Cords connect its “Sky Screens” – on a bar on a tripod – to the digital “brain” at the bench.

Garmin’s Doppler Xero C1 is much smaller than the Oehler 35P bench unit, has no screens or cables.

Ken Oehler and his wife Margie have given much to the shooting industry. The 35P proved such a hit, it was resurrected after Oehler’s Model 43 arrived. Mine has a permanent home. Set-up tips: Space screens precisely. A bullet at 2,800 fps spends 1/700 second between screens 4 feet apart, so a slight error in that span skews the numbers. To shield screens from muzzle blast, the first should be at least 10 feet in front of the rifle. As chronograph eyes aren’t bullet-proof, keep bullet paths at least 4 inches above them.

Handloading the wildcat .30 Gibbs, Wayne used a chronograph to get reasonable velocities, pressures.

The next big development in chronographs dates to 1842 studies by Austrian physicist Christian Doppler. His observations of shifts in wave frequency from moving objects led, after WW II, to the radar gun in police vehicles. By the 1970s, weather forecasts were using radar. The first Doppler unit I saw for shooters had a television-size screen. Reading bullets continuously as they sped downrange, it registered changes in ballistic coefficients over long flights. Hornady’s Heat Shield bullet tip resulted.

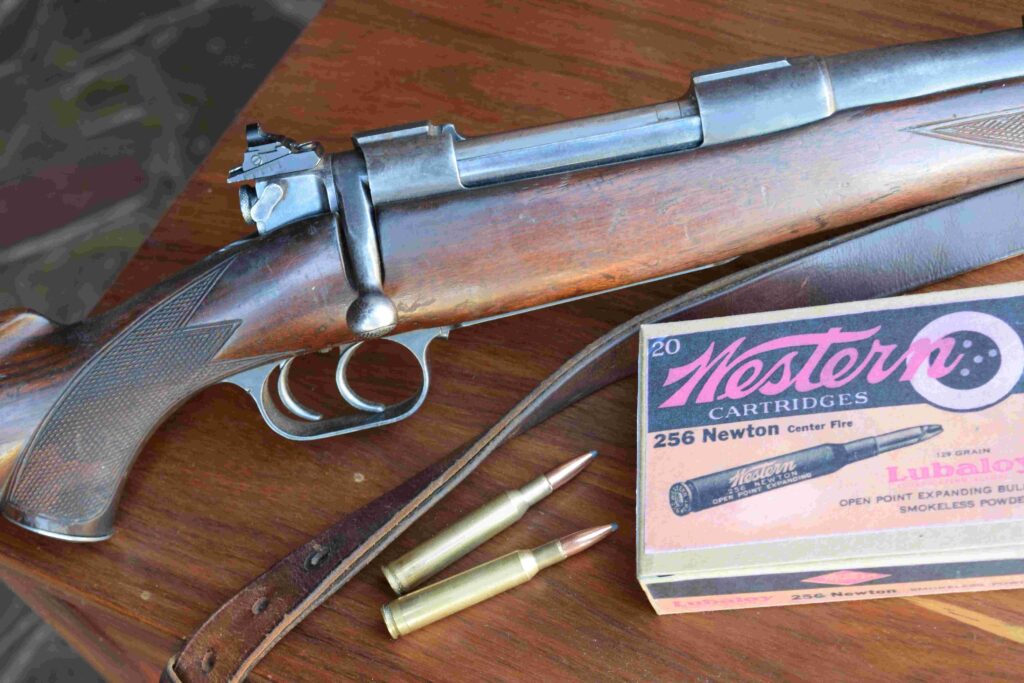

With a chronograph the obsolete .256 Newton (here: a Newton rifle) can be loaded to rival the 6.5 Cm.

LabRadar was first with a Doppler chronograph for handloaders. Powered by six AA batteries, it reads from 65 to 5,000 fps, continuously to 100 yards. So it can clock slow handgun bullets, even air-gun pellets. And, yes, arrows! Bluetooth-friendly, it can mine data from other digital instruments, like the Kestrel ballistic computer and advanced optics.

Garmin followed the LabRadar unit with its smaller, lighter Xero C1 – and LabRadar announced its compact, rechargeable LX version to compete. Yet to use the LX, I’ve been working recently with the Garmin Xero C1. Compact enough to slip into a jacket pocket, it weighs less than a turkey sandwich. Its display packs a lot of information into a small but eminently readable summary. The unit’s opposite face, blank as the side of a lunch-pail, faces the target. A short tripod (included) attaches to the C1’s belly on 1/4-20 threads. The Power, Menu and Scroll buttons are on top. A left-side USB-C port accepts a cable to charge the lithium-ion battery.

Wayne is using his Garmin Xero C1 to check factory data on Nosler’s new Whitetail Country loads.

I printed the instrument’s comprehensive manual, available at garmin.com/manuals/xeroC1. But tech-savvy shooters will hardly need it. The Xero C1 is easy to use, even intuitive! Select the appropriate “mode”: rifle, pistol, bow or “other.” Enter the projectile’s weight if you want energy as well as velocity in your results. Set the chronograph on the bench (or next to you, prone) 5 to 15 inches from the rifle and about that far behind the muzzle. Unlike traditional chronographs, Doppler units pick up the bullet’s track from behind; you needn’t shoot through or over a screen. The Xero C1 has no cables, requires no camera tripod or 15-foot apron in front of the rifle. It reads reliably in a wide range of light conditions and won’t collapse in wind.

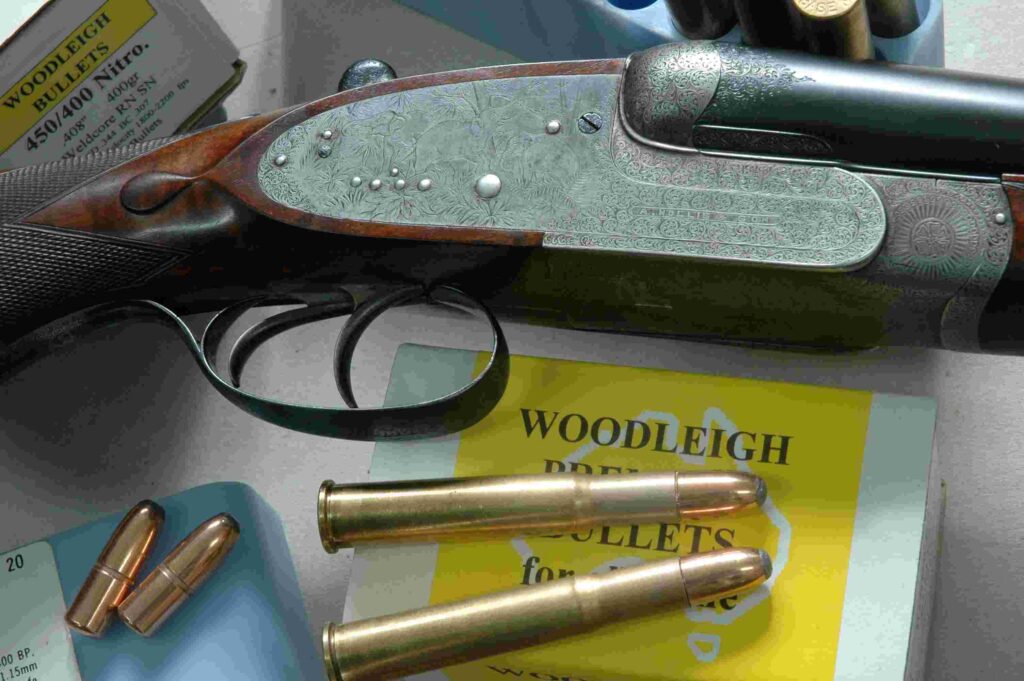

Data for early dangerous-game cartridges, handloaded and not, can be hard to find. Use a chronograph!

Setup is as fast as taking a rifle from a hard case. Targets should be at least 20 yards away. You don’t have to aim the unit precisely; just face it downrange. You’re smart to keep any Doppler instrument from the blast of brakes and ported muzzles. Pistols are best fired from 5 to 15 inches above the Xero C1.

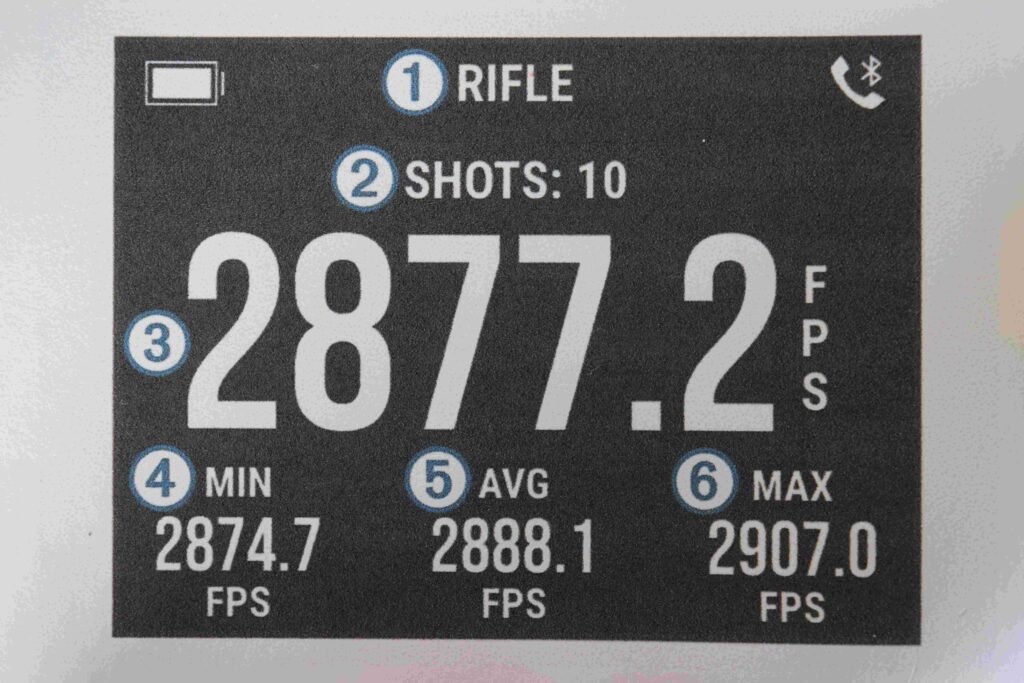

The Garmin’s display shows the mode, number of shots recorded and velocity of the most recent, also minimum (lowest), average and maximum (highest) velocity. Cycling through the data fields, you get extreme spread, energy, even the power factor. Standard deviation too. In math-speak, that’s the positive square root of the variance, the sum of the squares of deviations from the mean (average) velocity divided by a number one less than the number of shots fired. Boiled bare, a high SD indicates a lot of variability in your data. A low SD tells you most readings are close to the mean – which is what you want. Low SDs make for a neat and narrow bell curve and, presumably, more consistent shot placement. Better accuracy.

Beside you on the bench or mat, the Garmin Xero C1 instantly delivers important data after each shot.

Summaries of stored strings remain available from the Xero C1’s Menu under “history.” You can change units of measure, back-light brightness, even language on the display. To conserve battery during a pause in a string, you can stop recording temporarily with Menu and Power buttons, then resume. You can also delete shots and change data fields during the session. A ShotView app for your smart-phone is available, so you can view there data stored on the C1.

The .280 Ackley was long a wildcat. Chronograph new factory ammo for data to jump-start handloads.

You needn’t handload to appreciate Doppler radar and Gamin’s Xero C1. Check factory loads to get actual data from your barrel. Note data from accurate ammo to focus your search for new loads. And find out all you’ve been missing before you got a chronograph – a truly convenient chronograph!