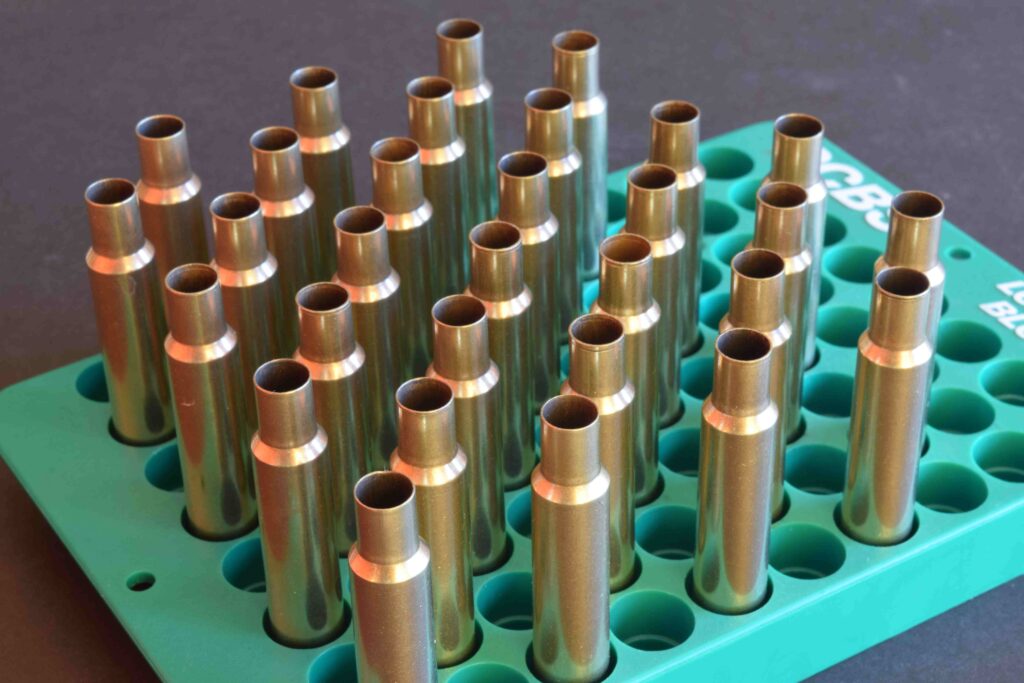

Clean, polished cases slip easily into dies and chambers, and protect both. They also reflect well on you!

Not all handloaders have work-spaces that match the gleam of surgeries, or benches and shelves crowded with spanking-new presses, die sets, tools and gauges.

But all handloading projects have the same product: ammunition. However constrained by space or budget, anyone who works a press handle can turn out cartridges that look like new. Shine is a shower, shave and clean shirt on brass, a sign of care and professional attention to detail. It’s what you admire in a motorist who keeps his or her vintage automobile clean and waxed, a neighbor whose house always looks freshly painted.

Finished cartridges tell much about who you are. Making them shine is worth a bit of effort.

The most visible component of a cartridge, and its only re-usable component, is the case. While steel and aluminum hulls serve for some times of ammo, the best and most common cases are of brass. Typical cartridge brass comprises 70 percent copper, 30 percent zinc. It is strong, ductile and corrosion-resistant. Exposure to weather can dull it and darken it. Grit can scratch it. Water can spot it. Oils from your skin can leave your fingerprints on it. But clean and stored in boxes, well-made brass can remain new-looking for decades.

If you care not about the inside of your cases, and have only a few to brighten up, lemon juice in a paste with baking soda should suffice. Or equal parts salt, vinegar and flour. Or catsup. Think of these as acid-plaster facials. After an hour, rinse cases thoroughly with warm, soapy water. Then rub them dry. I’ve not used metal polish on cartridge brass. After all, the case is a pressure vessel! While judicious use of mild abrasives shouldn’t weaken it or materially change wall thickness, I loath the idea of scratching it, no matter how finely.

You’ll stand a little taller boxing handloads that sparkle like jewels. Still, the benefits of brilliant cases aren’t just cosmetic. Surface dirt and debris can scratch dies and chambers and cause malfunctions in firearms. Bare, self-lubricating brass feeds and ejects eagerly. A bright case interior ensures there’s no powder or primer residue to foul or score your barrel, or impede ignition.

I wasn’t always a neat-nik at the bench. Early on, the only cleaning my cases got was a rag-wipe just before lubing and sizing, and another afterward to remove excess lube. It wasn’t enough. Pressing the mouth of each case on my lube pad to ease passage of the expander button left a ring of lube the rag failed to remove from the case mouth. During charging, powder too often stuck to it. The bullet then shoved it, with residue left in the neck, down into the case. Dry lube nixed the greasy ring but still left gunk in the neck. Eventually I wised up and used Q-Tip or a smaller-than-neck-diameter swab after sizing to pull out excess lube and ensure the neck was clean. Each bullet then got the same grip from the case, and the same start. The result was worth the brief additional step.

Next, to clean old, stained cases inside and out, I bought a small Lyman 600 Turbo Tumbler. But after three hours in the vibrating tub with crushed walnut hulls, a double handful of ’06 brass the color of strong tea emerged with only a dull glow. What the untreated walnut bits failed to remove was the patina of age – oxidation that over time turns copper greenish-brown. This discoloring is like bluing on steel, the result of a surface reaction that can prevent further, more damaging corrosion. Old copper can also take on a blue-green hue called verdigris, from the French vert de gris, meaning “green of grey.” You’ll see it on bronze statues after their long exposure to weather. It also afflicts cartridges kept in leather belt loops or pouches, a result of the action of tanning residues. Like firearms, ammunition is best stored apart from leather.

While discoloration alone doesn’t weaken brass, it can attend other problems that do. Cases that have turned chocolate with age may lack the elasticity that prevents splits. Most neck and shoulder splits I’ve seen were in aging brass. Oddly enough, I’ve lost as many new cases as old to circumferential splits forward of the web.

When I was young, some military ammunition predating the Great War was still floating around. It contained mercuric primers to ensure ignition in early smokeless loads. After firing, mercury residue attacked the zinc in the brass, weakening cases and causing splits. Non-mercuric primers for .30-40 Krag loads arrived in 1898. But their potassium chlorate corroded barrels! In 1927 Remington came up with its non-mercuric, non-corrosive Kleanbore priming. Peters’ Rustless and Winchester’s Staynless followed.

There’s no redemption for brass savaged by mercury.

Modern centerfire rifle and handgun cases can last for many firings if you don’t mash the throttle. But before they’re too tired to grip primers tightly or keep necks from cracking, they’ll warrant a cleaning or two. While walnut-shell chips, crushed corn cobs and other dry media can polish them inside and out, I’ve found “wet cleaning” more effective.

My Lyman Cyclone Rotary Tumbler for this operation has greater capacity than my dry tumbler. A 110-volt motor on a timer powers two rollers that rotate a drum containing the brass. Lyman notes the drum works best half-full of cases, with an ounce of Lyman Turbo Sonic cleaning solution in just enough water to cover. Then there are the pins. Instead of walnut-hull chips, the Cyclone Rotary Tumbler scrubs cases with re-usable steel pins about a third of an inch long. “Add 5 pounds of pins per drum-load.”

Lyman outlines two cleaning methods. The first is to tumble fresh-fired cases 15 minutes in water and solution only, to remove debris that can score dies and make sizing difficult. Next, dry the cases, then size and de-prime. With the primer pockets now exposed, tumble the brass again, with water, solution and pins. An hour of jostling in that drum should leave cases looking new, inside and out.

The other protocol: Skip the 15-minute pre-wash. Size and de-prime the brass, then tumble it in the water/Sonic solution with pins. You’ll save the drying time between pre-wash and sizing, so you’ll finish sooner, even if you allow a few more minutes in the solution than if this were a second tumbling.

To pre-clean but avoid drying cases twice, you can dry-tumble first, then wet-tumble after sizing.

I used this routine recently to spruce up discolored .375 H&H and 7mm Dakota cases. After forty minutes of sparring with untreated corn cob bits in my Turbo Tumbler, the brass was debris-free. While treated media (chips coated with jeweler’s rouge, for example) brighten cases faster, standard media will suffice in a pre-scrub.

To my dry-prepped .375 and 7mm cases, I added .300 H&H, .30-06 and 6.5 Redding hulls I had decided needed no pre-cleaning, save a wipe to remove lube after sizing. The resulting pile of cases, most of them magnums, left me thinking I’d have to run two batches. But after the Rotary Tumbler drum had swallowed all eight boxes of large rifle cases, plus 5 pounds of pins and water and Turbo Sonic solution to cover, it was only half-full! As this level was what Lyman advised for best results, I snugged the lid on its gasket, laid the drum on its drive wheels and set the timer for an hour.

As dry tumbling had given disappointing results after three hours, I was surprised at a 50-minute check to lift a couple of gleaming .375 and 7mm cases from the solution. They looked like new! With the Cyclone kit’s two polymer screens over a pail, I emptied the drum. The first screen caught only cartridge cases. The finer screen snared the pins. A warm-water rinse of the drum and the cases dislodged most pins that had clung to the brass. Still, it’s a good idea to check all cases individually with a flash-hole cleaner or a drill bit of proper size. I found one pin bridged in the neck of a 6.5 Redding case. Shaking water off cases and spreading them on dry towels readied them for baking sheets in the oven, where, with the pins, they finished drying on “low.”

Some handloaders advise using distilled water for wet-tumbling and rinsing cases. My tap water left no spotting.

In my view, wet-cleaning sized brass is the best way to bring shine back to cartridge cases dulled by time, stains and exposure to moisture and tanning chemicals. The wide maw and big belly of Lyman’s Cyclone Rotary Tumbler drum welcome batches of 100 rifle cases. The machine disgorges dazzling brass. I suspect high-quality wet tumblers of other manufacture deliver like results.

To be fair, some dry tumblers feature bigger bowls than that on my 600 Turbo. But no matter the size of – or media used in – dry tumblers, you’ll get bright, squeaky-clean inside and outside surfaces of fired cases quickest by rattling them around in wet solution with pins.

For case-cleaning and other handloading needs, you can’t do better than shop Midsouth Shooters Supply!

Sidebar: Bullets too?

Can bullets be polished in a tumbler? Well, yes. As bullets are a “one-time use” component, and most are nicely finished in manufacture, there’s arguably little sense in polishing them. But I have come upon factory-fresh bullets with dull or spotted exteriors. Most bullet jackets are of gilding metal, typically now 95 percent copper, 5 percent zinc. “Solid copper” bullets may be intentionally alloyed; even “pure” copper bullets contain trace amounts of other metals. Because bullets of lead or copper are much heavier than cartridge cases, you’ll reach practical drum capacity by weight sooner than you will by volume. Of course, if you tumble bullets, you’ll do so before you seat them in charged cases! Never tumble primed cases or loaded ammunition!

Sidebar: The color of ductility

Brass, the union of copper and zinc, appeared in China around 500 B.C., in the Middle East 200 years later. Not until the 16th century were the two metals properly alloyed in a practice called speltering.

A cartridge case must be ductile – that is, stretch and contract without cracking. Under the press of powder gas, it must iron itself to the chamber, then relax to allow easy extraction. It must next conform to the squeeze of a die, open its mouth to accept a bullet, then hug the bullet shank tightly. At each step, and in rough handling afterward, the case must maintain its shape, surface gloss and required dimensions!

After several firings and re-sizings, brass cases “work-harden” and become brittle. You can bring back their ductility by annealing: heating, then rapidly quenching the front half of the case. I use a butane flame applied to cases standing in half an inch of cold water, tipping each case over as neck and shoulder turn a dull cherry-red. Yes, reaction of brass to this heat-quench treatment is opposite that of steel.

Annealing colors brass. A dark tarnishing up front is easier to polish out than is a blue-white hue, which appears often on military cases, less commonly on commercial brass. As it marks a useful change in the metal’s structure, it doesn’t strike me as any more unsightly than a case-colored rifle receiver.