Superior handloads start with cases uniform in dimension and clean enough

All handloads start with the cartridge case. That little metal cup is a pretty recent development, as gunpowder dates to 9th-century China, and it was in 1267 that England’s Roger Bacon, wrote: “From the violence of that salt called saltpeter [with sulfur and willow charcoal, came a blast] exceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning.”

Six centuries would pass before metallic cartridges become practical. In 1848 New York inventor Walter Hunt designed a repeating rifle whose bullet had powder in its cork-capped hollow base. A primer fed by a pillbox device shot sparks through the cork. Lacking money to advance his rifle, Hunt sold patent rights to George Arrowsmith, who hired Lewis Jennings to improve it. Arrowsmith then peddled the rifle for $100,000 to railroad magnate Courtland Palmer. He asked Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson to add a a copper base to Hunt’s “Rocket Ball” and put $10,000 toward a partnership with them. The trio sold out in 1855 to 40 New York and New Haven investors. One, Oliver Winchester, became director of the new Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. When two years later it faced receivership, he bought all assets for $40,000 to found the New Haven Arms Company. In 1860 his gunsmith, B. Tyler Henry, patented a rifle he had fashioned from the Hunt repeater.

The .44 Henry was a rimfire cartridge, its priming in a folded rim that also arrested the case at the chamber lip. It’s a design still used for small, low-pressure rounds – famously the .22 Long Rifle, an 1887 development that followed Smith & Wesson’s work of the 1850s.

Centerfire cartridges appeared after our Civil War. The sturdy brass case head holds the primer, a thin-metal cup whose explosive compound is crushed by the rifle’s hammer or striker against an internal anvil in the cup (Boxer) or case (Berdan). Unlike rimfire cases, a centerfire case can be re-used after the spent primer is punched out and the case, expanded by firing, is squeezed in a die to original dimensions.

Nearly all modern commercial centerfire cases are of brass and “solid-head” (not “balloon-head”) design. Steel cases sometimes used in military ammunition, and aluminum cases for mild pistol loads, are not suitable for re-loading.

Even new brass is best inspected to ensure it’s free of dents and burrs. Running new cases into a sizing die shouldn’t be necessary. On the other hand, cases properly sized in manufacture suffer no undue “working” in that step, which can iron out small imperfections and help ensure a uniform case lot.

Keep cases clean! At the range, don’t eject them onto the ground or gritty surfaces. Scrounging spent cases, tap them, mouth down, on wood to ensure there’s no loose grit inside. Wipe the exterior with a cloth. Tiny particles trapped by case lube can scratch dies and cases. I use a nylon bore brush to clean the insides of case necks – and to apply dry graphite lube to ease passage of the sizing die’s expander ball.

A case tumbler with walnut-hull or similar polishing media can bring the shine back to discolored cases. I de-prime first, so primer pockets get scrubbed. Then I check with my pocket/flash hole cleaner for media that might remain to obstruct the primer or spark. For large batches of cases, or those with stubborn patina, a turn in a rotating drum with liquid cleaner makes sense. My Lyman tumbler works well; but for fast results (if more steps) I turn to Lyman’s drum, and brass-specific liquid detergent.

You’re smart to use cases from the same source, as brass from one maker may differ in thickness from that of another. Thick brass, relative to that of a case with thinner walls, has less capacity, given the same outside dimensions. Variation in capacity can yield differences in pressure and velocity. Accuracy is a measure of uniformity! That’s why Benchrest shooters batch cases by source and weight. Putting cases on a scale takes little time. Set aside hulls more than .5 grain over or under the mean. Prepare at least 50 cases at a time so you can cull severely without denting your supply of finished cartridges.

Breech pressures in modern rifle cartridges commonly exceed 50,000 psi, stretching the brass at each firing. Some cases (like the long, tapered .300 H&H) stretch more than others. Hot loads add stretch and shorten case life! Periodic measuring tells you when to trim cases. A hand trimmer suffices; electric trimmers speed the process. If a case gets so long it presses hard against the chamber mouth, it can crimp the bullet, boosting pressures and reducing accuracy. Depending on the chamber, and how much the case has elongated, it may even prevent bolt closure. Set your case trimmer to take half a millimeter from the mouth of a case exactly the specified length for the cartridge. Trim all cases from that batch to that length. There’s nothing unsavory about a bottle-neck case trimmed a tad short. Removing a little extra, you’ll get several firings before you must trim again. The exception: straight rimless cases that headspace on the case mouth. These must be kept at SAAMI-specified length.

Deburr the case mouth inside and out with a deburring tool – one of the least expensive and least appreciated of bench tools. A tapered lip eases bullet seating and chambering and helps ensure uniform neck tension. Remove only the burr; a couple of twists may be enough. Take care not to “sharpen” brass at the mouths of straight rimless cases that headspace up front. Leave a clean, square leading edge.

Some shooters who’ve seen every re-run of Law and Order spend evenings with ball micrometers measuring case-neck wall thickness. Measure four points around the neck. Variations here can reflect case wall variations not so easily gauged. Disparities of .0015 or greater in a neck call for outside neck-turning to make wall thickness uniform. My Sinclair outside-turning tool has a mandrel or spud that slips into the neck, centering it and establishing a gap for the blade. Rotate the case as you push it forward on the spud. Adjust the blade so it barely hits the “high spots” or thick places as the case is spun. Shaved spots appear bright. Ease the blade incrementally closer to the spud as you spin, so subsequent rotations gobble more brass. Stop as soon as the neck is uniformly bright, or just before. Wall thickness that’s exactly the same at every point around the neck ensures bullets will be gripped with uniform tension and cleanly released. Concentric cases orient themselves more uniformly in chambers and more easily enter “tight” or “match” (minimum-dimension) chambers that can produce superior accuracy. A hull with no wall variation also collapses uniformly in the sizing die.

Inside-turning is another option. You’ll need a different tool. This operation removes “donuts,” as well as brass shoved forward by repeated firings.

Inspecting a batch of cases, attend to both ends. Most flash-holes in rifle cartridges are punched to .082. Check with a #45 wire-size drill bit. Some hulls – the PPCs, 6mm BR and Match cases for the .223 Remington – have .060 flash-holes. While off-center flash-holes have yet to bring me grief, I batch such cases apart from those with important tasks, like hitting X-rings or making hard-won shots at game.

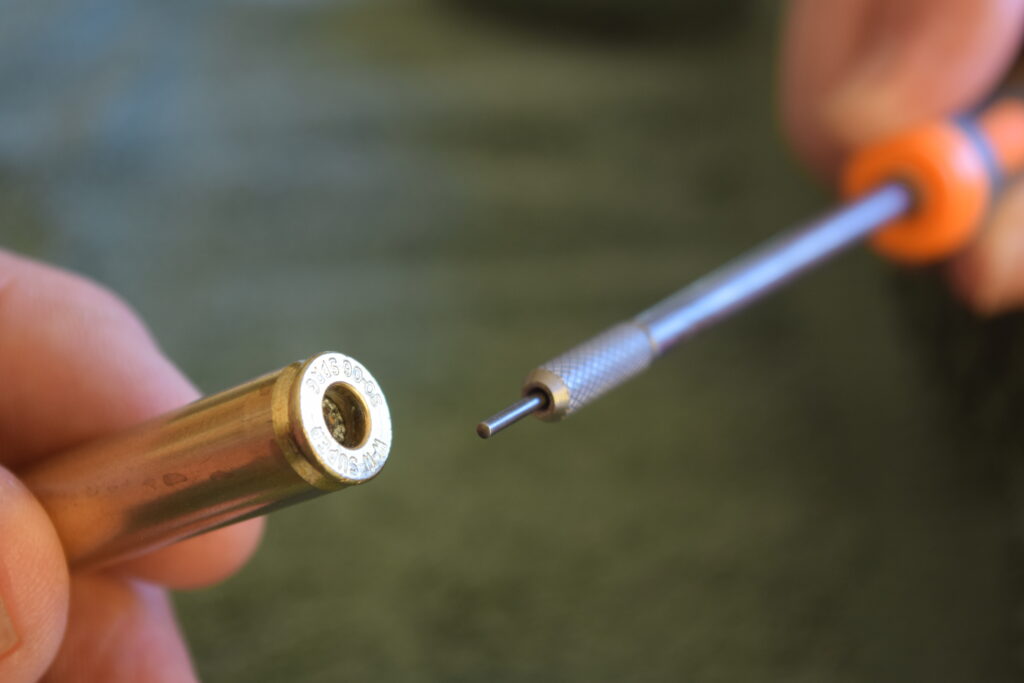

I’m told Norma and Lapua drill flash-holes in Match cases, but punching is far more common. A flash-hole deburring tool inserted from the case mouth can “clean up” the ragged edges of punched holes. A depth gauge, set on the case mouth, helps with this operation. Use caution. Take just the burr; don’t cut into the case web! No, deburring flash-holes isn’t as necessary as seating primers right-side up. But neat, uniform holes are one more step toward uniformity in your cartridges. A detail worth minding if you want the best accuracy from your handloads!

Most tools needed to help you inspect, clean, trim and maintain cases so they look good and give you long service are inexpensive. They’re available from sources like Midsouth Shooters Supply, where you’ll find a wide selection of handloading components – plus competitive prices and quick delivery that brings serious handloaders back!