This mechanism is at the heart of a rifle reloading setup, and options abound. Here’s what really matters, and how to know what you need (and what you don’t). READ MORE

Glen Zediker

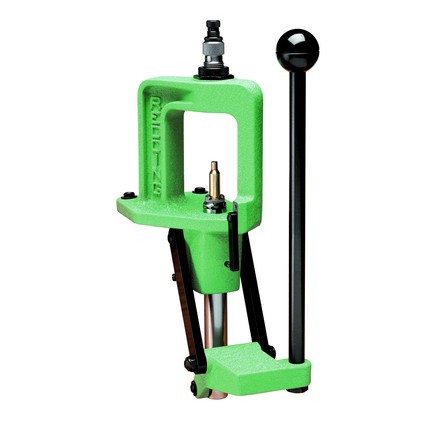

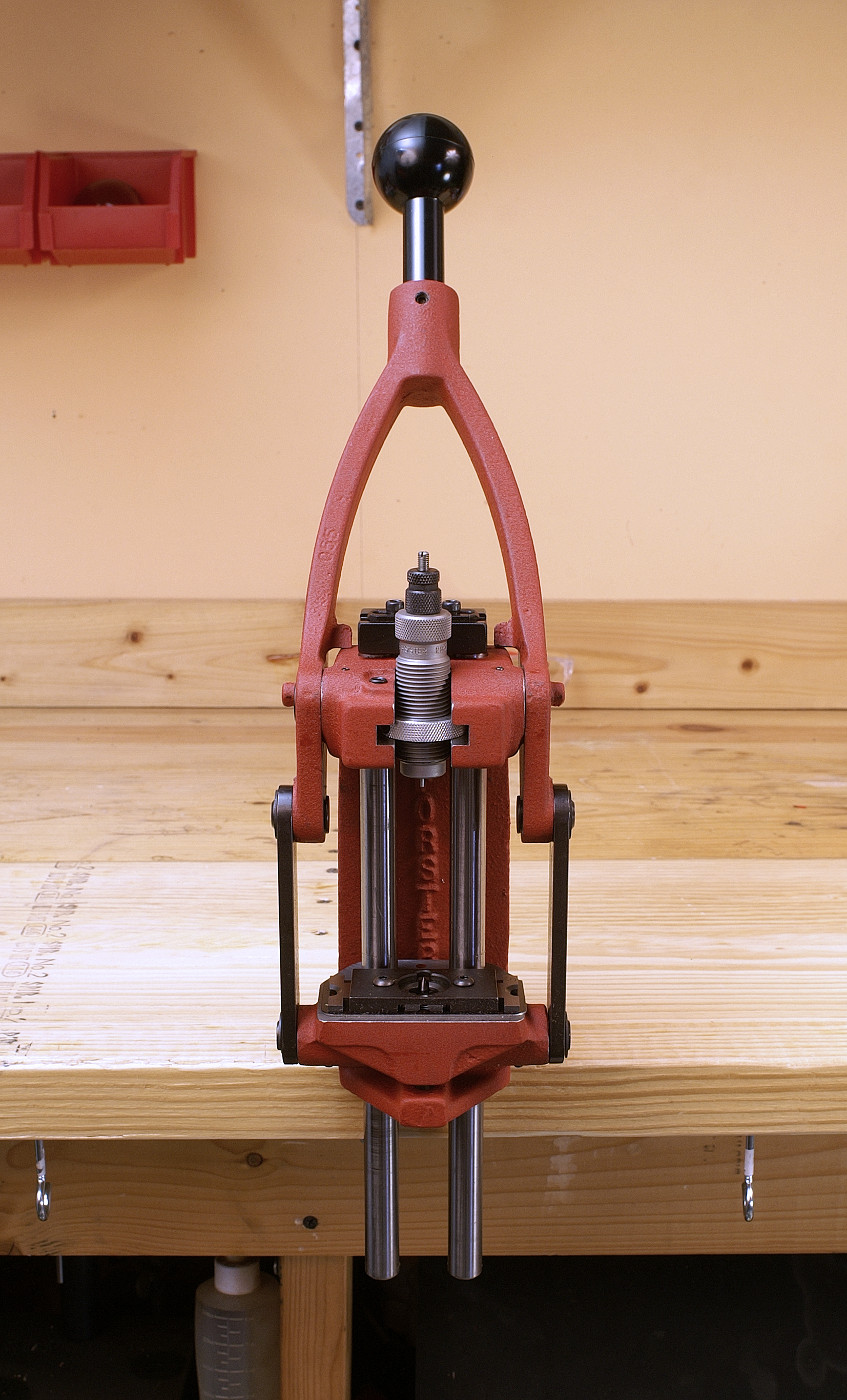

A press is usually the first thing mentioned to a new handloader when the question is “What do I need to get?” Can’t, pretty much, load without one. The press houses the sizing and seating dies, and other tooling, and can also serve as a primer seater.

Shopping for presses shows a big range of prices, and sizes (usually related), and also some type or style options. The press type I’m going to be discussing here in this bit is called a “single-stage,” and it gets that name because there’s one receptacle for any thread-in appliance, such as a sizing die. It can then perform one single operation.

The standard receptacle has 7/8-14 threads.

The main option is the size of the press, which means the press body size, ram extension distance, and handle stroke arc and length.

When is a “big” press best? When operations require big leverage. Or for really big cartridges. Or when using a press to perform an operation that’s more power hungry than case resizing or bullet seating. Given a choice of “small,” “medium,” or “large,” as many times, I’d suggest going at least “medium.” Unless, that is, you have compelling reasons to get another. Don’t underpower yourself. On the other hand, you decidedly do not (usually) need a tower of power, and might even find it’s kind of in the way.

I like the operational efficiency of a smaller press, one that doesn’t have a big stroke arc. In sitting and doing a large number of press ops I really notice the additional effort of cycling a bigger press. However! There’s also sometimes no substitute for torque. Sizing unwieldy military cases, for instance, on a honking press takes a less effort from the self.

As I’ve mentioned in these pages before, I also like being able to move my tooling around on my workbench bench, or even into another environment. Smaller presses are easier to tote and easier to mount.

It really depends on what you are loading for. A smaller, shorter case, like a .223 Rem. or 6.5 Creedmoor, or a bigger round like .30-06 or .338 Lapua? As with many things, most things maybe, going bigger to start is a better investment. By “bigger” I mean a press with a window opening big enough (or that’s what I call the open area available between the shellholder and press top) and stroke long enough to handle the longest cartridge you might tool it up for.

Does weight matter? Not really. A heavier press doesn’t necessarily mean it’s more rigid or effective (or not for that reason). Modern alloys are every bit as good as cast iron, and there was a time when I was uncertain of that. Speaking more of materials, cast iron has been, and honestly still is, the “quality” material used in press construction. Cast iron is rigid. This material is, well, cast into the essential shape of a press, and then final finished (faced, drilled, tapped, and so on). The only part of a cast iron press that’s cast iron is the body of the press. Aluminum, other alloys, or steel are used to make the linkage and handle, and other pieces parts. Cast iron can’t really bend which means it can’t warp. Cast iron just breaks when it hits its limit of integrity. It can flex (just a little) but returns perfectly. Alloys or metal combinations used in the manufacture of presses nowadays are pretty much the same in performance and behavior under pressure as cast iron. The essential compositions vary from maker to maker. I have cast alloy body presses and others that are machined from aluminum stock. These are all lighter but just as rigid as cast iron. Press architecture has a whopping lot to do with how rigid it is (and its leverage has a lot to do with linkage engineering).

What matters much is the sturdiness of the bench and how well the press is mounted to it. What might feel like press flex is liable to be in the bench, not the press, or in the press handle itself.

Alignment — straightness — matters in a press. This is the concentric relationship between the threaded tool receptacle and the press ram. They, ideally, will be dead on, zero. Then of course the die has to be “straight,” with its threads correctly cut and insides reamed on center. And then the shellholder arrangement has to likewise be dead centered with everything else. There is a lot of play in a 14 pitch thread. All this means is that a “straight” press doesn’t automatically mean you’ll not see issues with tooling concentricity. More in another article shortly, but at the least the press (body and ram) should not contribute to create concentricity miscues. I know of no manufacturer that doesn’t claim correct alignment in its product, but I also don’t know if it’s something they’ll warrant.

Presses do require, or at least should get, maintenance. Keep it clean! There’s a lot of abrasive potential from incendiary residues, and that will, not may, wear the mechanisms. I have often and for many years recommended a separate decapping or depriming station.

CHECK OUT DECAPPING TOOLS HERE

The preceding is a adapted from information contained in from Glen’s books Top-Grade Ammo and Handloading For Competition. Available HERE at Midsouth Shooters Supply. Visit ZedikerPublishing.com for more information on the book itself, and also free article downloads.