The following is a specially-adapted excerpt from the forthcoming book,” Top-Grade Ammo,” by author Glen Zediker, owner of Zediker Publishing. Click here to order.

Last time I gave a caution about respecting one of the differences between semi-auto and bolt-action rifles, and that was with respect to propellant burn rates. The summary reason for that is that different rate propellants will “peak” at different areas as the expanding gases and the bullet travel through the bore. Slower-burning propellants peak farther, and that means more pressure is available at the gas port location in an AR-15, for instance, as the bullet passes it. If the system is oversupplied, then the system is overworked.

Compared to ideal function when gas supply is delivered as engineered, mistimed peak pressures can result in the bolt unlocking too quickly and excessive bolt carrier velocity rearward. The system just gets hit too hard. The extractor tries to yank the case out of the chamber too soon, before the case is released from its grip on the chamber walls (from being expanded through firing). Spent-case condition shows a measurably more abused hull. Probably the worst popular example of these effects is the M1A. I’m doing an entire column or two on reloading for this beast. Essentially, a spent case from an M1A will show dimensions that don’t seem possible. These come from the bolt unlocking too quickly. AR-15s actually handle excessive pressure better than some other designs.

Always keep in mind that this is all happening in about 2 milliseconds. Average time a bullet spends in the barrel, for most modern centerfire rounds, is 0.002 seconds. Timing is everything.

Keeping in mind the behavior of a pressure curve, which is like a wave cresting, factors that influence the amount of gas-port pressure, using the same load, include barrel length, gas-port size, and gas-port location. When the bullet is sealing the bore, the longer the barrel, the more pressure is contained for a longer time. The smaller or larger the gas port size, the slower or faster the gas enters the system. The farther back or forward the port is located, the sooner or later. Bullet weight is a factor also: heavier bullets accelerate more slowly (and also the reason heavy bullets erode the chamber throat more than lighter bullets).

And, the amount of volume inside the bore has a huge influence on all this. That matters when we’re using another caliber than .224 in an AR-15 or .308 in a big-chassis AR (like an SR-25). For instance, in that rifle chambered for .243 Win., but retaining the gas system specifications (gas port size and location) of the .308 Win.–chambered rifle, there’s way more pressure only because there’s less space, less volume, in the bore. The opposite is usually true when we’re running an AR-15 with a larger caliber bullet.

Selecting a propellant with a suitable burning rate, which, again, is something in the vicinity of H4895, is really the only thing we can do on the loading bench to ensure that we’re not contributing to these symptoms. Beyond that, dealing with excessive pressure gets technical.

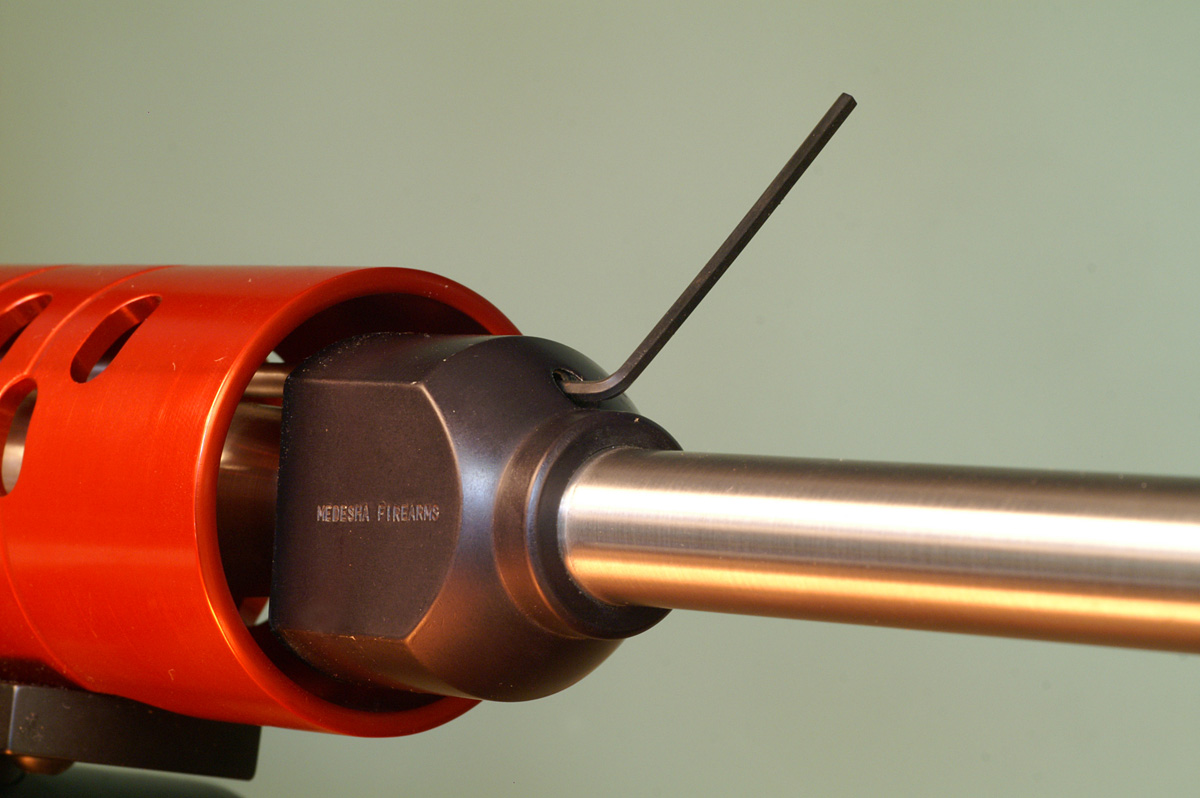

All my NRA Match Rifles, which usually have 26-inch barrels, get their gas ports moved forward one to two inches. These, of course, are custom-barreled. I also usually install an adjustable gas manifold.

Moving the port forward effectively delays the wave of gas moving through the bore, kind of repositioning its peak with respect to its outlet; there is more space available for expanding gases. It also allows a little slower-burning propellant, which can take more advantage of the longer barrel. It’s common in a similarly constructed AR-10 to get a port moved as much as 5 inches forward to accommodate a .243 Win. or .260 Rem. chambering.

The adjustable manifold allows some tuning. There are essentially two forms these take. One way is to restrict or limit the through-flow; the other just bleeds it off. I like the first kind the best.

Also, I have searched far and wide for a consensus on gas-port sizes, and came up empty.

All this changes with different chamberings and rifle configurations. Carbine-length barrels are particularly sensitive to port pressure because the port is located farther back.

There are a few surefire things that will alert you when your rifle is exhibiting “over-function” symptoms, such as spent-case condition showing excessively blown (extended) case shoulders, extractor marks on the case rim, and a generally explosive sensation in functioning.

In a more extreme circumstance, an over-accelerated carrier can “bounce” back from its rearmost travel so quickly that a round can’t present itself in time to be picked up by the bolt, or the bolt stop can’t engage quickly enough to hold the bolt carrier.

Sometimes what appears to be a “light” load is actually not. I’ve seen excess pressure leave a spent case in the chamber because the extractor lost its grip, and I’ve seen chunks pulled right off case rims. That’s severe. That’s also another cause for the “short-stroke” appearance of over-function: the extractor issue has slowed the carrier.

If you’re having any problems with “over-function,” solutions include retrofitting an adjustable manifold, increasing carrier mass, installing a stouter buffer spring. I do all those things on my rifles. Keep in mind that I am primarily a Service Rifle shooter, and I am trying to push an 80-grain bullet as fast as reasonably possible from a 20-inch barrel that can’t get the modifications mentioned. I know a thing or three about delaying bolt unlocking — I’ll cover more on this topic if you all want to know.

Sources:

663 West 2nd Ave., Suite 16

Mesa, AZ 85210

(480) 833-9876

10326 E. Adobe Rd.

Mesa, AZ 85207

(480) 986-5876